ONAI – Climate Change Studies Organisation for Afghanistan

Introduction

The current fragile political situation in Afghanistan has not only humanitarian and economic consequences for the country itself, but it could result in a spread of insecurity and destabilization of the region between Central and South Asia, with disruption of regional economic cooperation efforts between the regional countries that have started in the recent years. In particular, the regional energy projects experienced unprecedented progress during the last two decades. Projects such as CASA-1000, the TAPI gas pipeline, TAP, and TUTAP were promising endeavors to facilitate cooperation among the regional countries of Central and South Asia and extend this cooperation to other sectors, such as trade and transport.Due to its geographical location, Afghanistan is considered the main linkage to the two strategic regions- Central and South Asia. However, the recent regime change resulting in a takeover by the Taliban has caused uncertainties regarding the implementation of the ongoing and planned regional projects.

This blog will assess the implication of potential long-term isolation of Afghanistan due to the recent taking over by the Taliban on the ongoing and future regional energy cooperation between Central and South Asia.

Background

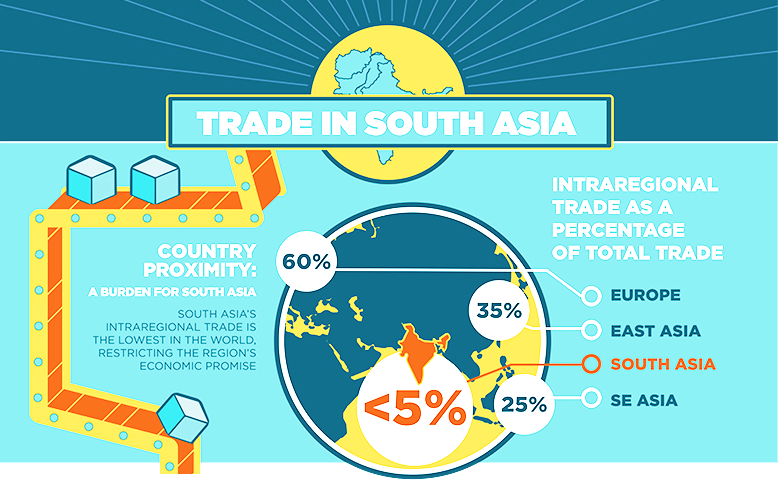

According to the World Bank (2017), South Asia is one of the least integrated regions in the world, where the total share of intra-regional trade is five percent of the total regional trade. Compared to South Asia, the ASEAN regional trade accounts for 25 percent of total trade (ibid).

Figure 1: Intra-regional trade in South Asia (World Bank, 2017)

Despite the fact that the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was established in 1985 to enhance regional cooperation in South Asia, the organization is labeled by many experts as a study driven institution that has not realized that “real cooperation does not rest in intention but implementation” (Sridharan, 2007). Even the SAARC Energy Centre (SEC) establishment in 2006 could not move towards the creation of the intended regional energy market.

Scholars believe that the existing disagreement in SAARC is rooted on a bilateral level (ibid), with the Kashmir conflict between India and Pakistan at the center. Moreover, the multi-faceted conflict between Afghanistan and Pakistan and other South Asian countries has caused the current stagnation within SAARC. In addition to the political issues on a regional level, the countries of South Asia also suffered from country-specific matters on a policy and implementation level that impeded effective steps towards regional cooperation (World Bank, 2008; Singh et al.,2015).

Under consideration of the political circumstances in South Asia, there were two options- continuation of the status quo or searching for new ways of cooperation that will result in economic growth and prosperity through cooperation in key areas, such as the energy sector. To overcome this stagnation, an extension of the cooperation efforts to Central Asia was proposed, focusing on projects in the energy sector. In that regard, the ESMAP[1] report from 2008 published by the World Bank can be viewed as one of the key documents of the extended regional energy cooperation between Central and South Asia, with Afghanistan as the main transit route (World Bank, 2008).

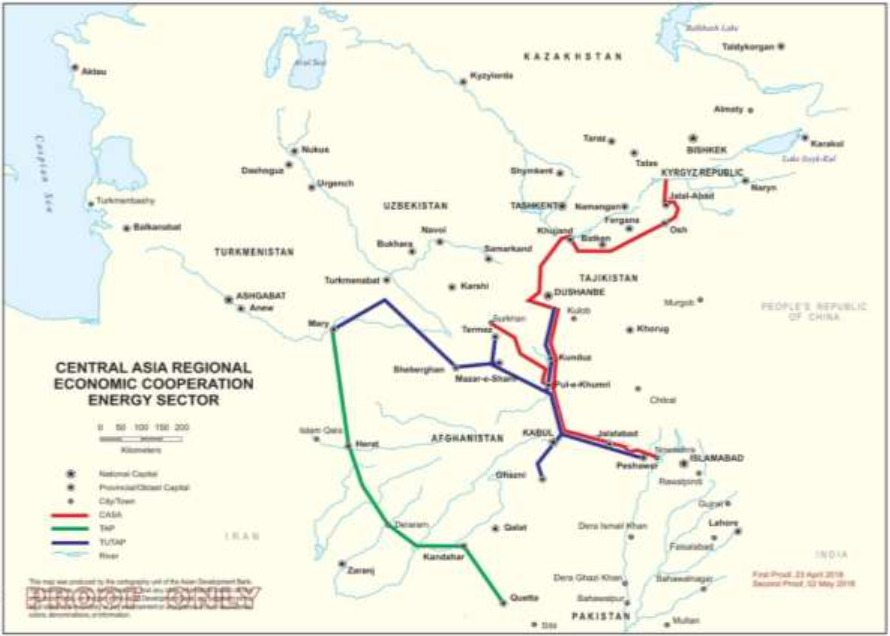

The vision of the creation of Central Asia South Asia Electricity Market (CASAREM) started with the initiation and planning of the CASA 1000 project, which aims to transmit power from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pakistan with a total capacity of 1,3000 MW. The project is currently under implementation, and the scheduled completion is 2024. Another critical project is the Turkmenistan- Afghanistan- Pakistan (TAP) 500 kV interconnection that shall provide up to 4,000 MW of electricity to Afghanistan and Pakistan (Ministry of Finance, 2016). In addition, the TUTAP (Tajikistan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan- Afghanistan-Pakistan Interconnection) concept envisages the supply of surplus electricity[2] from Central Asia to Pakistan (Asian Development Bank, 2014).

Figure 2: Central Asia- South Asia Power Projects (CAREC, 20

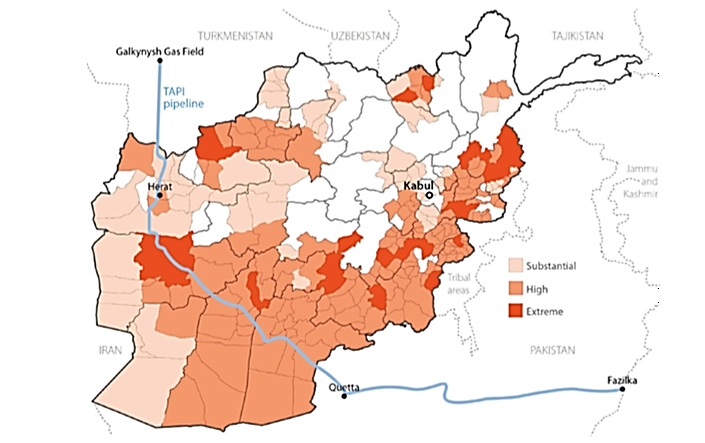

The 1,600 km TAPI gas pipeline, which is the first interregional project involving India, shall provide 33 billion cubic meters (BCM) of natural gas from Turkmenistan to Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India (European Union, 2016). The implementation of Phase 1[3] of TAPI (Asian Development Bank, 2020), supported by ADB, has started in Turkmenistan, and Afghanistan has inaugurated the start of works on Afghanistan soil in February 2018 (Pannier, 2018).

Figure 3: The TAPI Gas Pipeline (European Union, 2016)

The ongoing interregional projects are at a different stage of implementation and the regional countries, despite existing financial, economic, and also security-related impediments, view this interdependency approach as a win-win situation for all involved countries. They shall not only facilitate energy security and economic development but also pave the way for political stability and peacebuilding in the broader region.

However, the situation has changed with the collapse of the government in Afghanistan and taking over by the Taliban, who now have control over the Afghan territory. Although the Taliban have announced a caretaker government, no country has recognized their administration up to now. Despite the fact that the international community has requested the Taliban to consider the inclusivity aspect in their government, which comprises the consideration of all ethnic groups of the country and the inclusion of Afghan women in all levels of governance, up to now, the Taliban have not shown real intentions to accept the conditions of the international community.

The ongoing situation has a massive impact on the humanitarian situation of millions of Afghans, particularly women and children, but could also have a considerable impact on the political and economic situation of the broader region between South and Central Asia. The aforementioned regional energy projects also face an uncertain future in the light of recent developments in Afghanistan, which could have implications on the envisaged regional cooperation efforts between Central and South Asia if Afghanistan is politically and economically isolated.

In the following, the possible implication of Afghanistan’s isolation for regional energy cooperation is discussed.

Impact of Afghanistan’s possible long-term isolation on inter-regional energy trade between South and Central Asia

The taking over of Kabul on 15 August by the Taliban has changed the dynamics in the region between Central and South Asia entirely. Major financial institutions such as the World Bank[4] , the International Monetary Fund (IMF)[5] , and the Asian Development Bank have halted their operations in Afghanistan. As a consequence, all ongoing and planned development projects have been stopped since 15 August 2021.

The support to Afghanistan is limited to humanitarian assistance through the United Nations in order to prevent a humanitarian disaster during the upcoming winter. The current humanitarian crisis is exacerbated by a devastating drought throughout almost all country provinces, whereas over 14 million people suffer from food insecurity (World Food Programme, 2021).

No country within the international community has recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government of Afghanistan, and the United States has frozen all the country’s financial assets (Latifi, 2021). Possible recognition of the Taliban government is based on conditions, including forming an inclusive government, respecting human and women’s rights, and counterterrorism assurances (Watkins et al., 2021). International recognition is of the few remaining levers the United States and other countries can utilize to pressure the Taliban government (ibid). The frozen assets of over USD 9.5 billion (Latifi, 2021), although having enormous consequences for millions of Afghans, is another pressure tool of the international community to bring the Taliban on a path that conforms to international norms of the 21st century.

Even countries such as Pakistan, Qatar, Russia, Iran, and China, who had very close exchanges with the Taliban over the years, have not recognized the Taliban regime. The mentioned countries have not closed their diplomatic representation in Kabul, but as expressed by the Russian foreign minister Lavrov the international recognition “is at the present juncture not on the table” (Nichols, Psaledakis, 2021). India, an important stakeholder in the region, fears that the Taliban will allow the influx of fighters through Pakistan into Kashmir (NRP, 2021) and has indicated huge concerns about Taliban rule in Afghanistan. Therefore, diplomatic relations between New Delhi and the Taliban regime depend not only on the decision of international stakeholders but also on the regional dynamics between Pakistan and India and the developments in Kashmir.

The Central Asian countries have taken different paths in regards to relations and possible recognition of the Taliban. Whereas Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan have either met with the Taliban or even sent their envoys to Kabul, Tajikistan’s President has expressed his concern and openly criticized the lack of Tajik representative in the Taliban government.

The foreign minister of Uzbekistan visited Kabul last week with the aim, among others, to secure the planned bilateral projects, such as the Surkhan-Pole Khumri 500 kV transmission line and the railway projects from Mazar-e Sharif in Afghanistan to Peshawar that will open South Asian ports for Uzbek good (Eurasianet, 2021a). Turkmenistan has similar economic interests and has even met the Taliban beginning of this year and then shortly after the taking over of Kabul, discussing the implementation of TAPI and other projects (Eurasianet, 2021b) which indicates a very pragmatic approach on both sides focusing on economic gains.

Kyrgyzstan expressed in a statement from the President’s office its concerns over “the formation of a theocratic state “(Pannier, 2021); however, it also sent a delegation in September to Kabul who met the acting minister of the Taliban.

In contrast, Tajikistan that shares a long border with Afghanistan, is one of the main electricity exporters[6] to the country and a primary stakeholder in the CASA-1000 project, expressed its deep concerns over the Taliban and the Tajik President accused them of human rights abuses against the Tajik minority in the Panjsher valley (AlJazeera, 2021)[7] . The Taliban, in response, accused Tajikistan of interfering in Afghanistan’s internal affairs and dismissed the claims of the President (ibid). The relation between the neighbors remains charged with tensions, and if continued, it can be a real impediment to political and economic cooperation between the neighbors.

A recognition of the Taliban by the United States and their allies seem equal to the loss of another of the few remaining leverages over them and could increase the probability of continuing the Taliban’s repressive and exclusive governance form. This decision would open up the international stage for the Taliban without any tangible concessions regarding human and women rights and the formation of an inclusive government, which will worsen the situation of the people, particularly that of women and girls.

On the other side, continuing the current situation may result in a complete collapse of the Afghan economy. Without a recognized government in place, major international financial institutions and donor agencies involved in the regional projects will not be able to restart their activities and finance the projects where Afghanistan is a key transit route. This situation will not only impact Afghanistan but will also have an enormous impact on the economies of Central Asian countries, which are very much dependent on revenues from current and future regional energy projects. Moreover, this state will close the envisaged inter-regional cooperation between South and Central Asia for years, if not decades.

Furthermore, complete isolation of Afghanistan could also facilitate opening new sanctuaries for various militant groups who have agendas beyond the Afghan border. Considering the recent attacks of the ISIS-K in Kabul and other provinces, the threat is real and requires joint efforts from neighboring countries, regional powers, the US, and Europe.

However, the question remains on how to engage with the Taliban in this regard.

Conclusion & Recommendations

Taliban need international recognition to avoid political isolation as they experienced from 1996-2001 and prevent a complete collapse of the economy which will definitely cause internal challenges to their anyhow fragile governance which lacks support by the people.

The international community has announced certain conditions before assessing the recognition of the Taliban government in Kabul, where the formation of an inclusive government representing all sections of the Afghan society, the respect of human and women rights, freedom of speech and freedom of expression, the access of girls and women to education and maintaining of a vibrant civil society and a free media, build the fundamental pillars and that shall be uncompromisable. However, to ensure the implementation of the conditional recognition, it is necessary that a monitoring mechanism supervised by an independent international body led by the UN is place. A violation of the commitments made by the Taliban shall imply that the reconsideration and possibly deprivation of the recognition and freezing of the financial and development aid support to the Taliban.

Because Afghanistan will continue to depend on international aid for the following years, development aid is another substantial leverage for the international community to push through its demands.

Based on the mechanism above, which includes an independent and regular oversight of the commitments made by the Taliban, the international community could assess a conditional recognition, the recommencement of financial support, and the restart of national projects financed by international financing institutions and donor agencies.

Regarding regional projects, the international community may choose a different approach under consideration of the regional nature and the involvement of various parties. These projects have economic weight for the involved regional countries and are also of enormous political importance as the created interdependency can improve peace and security in the broader region.

A withdrawal from the regional projects may cause pressure on the Taliban in the short term, but in the long term, such a decision could negatively affect the economic and political climate of the region between Central and South Asia. The ongoing and future projects, in particular in the energy sector, have gone through years of planning and negotiation processes, and the international community and also the involved countries have spent millions of USD on the endeavors; therefore, it is not advantageous to withdraw from these projects at such as critical juncture just because of disagreements with a single party.

In contrast, these projects can be utilized as an additional pressure tool on the Taliban since they also signaled their support to these projects and, therefore, are willing to cooperate rather than seeing them in an isolated position.

Besides the major international donor, the regional countries could also conduct, in a coordinated manner, bilateral and multilateral talks with the Taliban. For the involved regional countries with substantial economic benefits from the energy trade, these projects are part of their long-term economic strategy for developing and opening new markets for their goods and services. Thus, they will seek ways for continuation of the projects and will coordinate their efforts with the international stakeholders to secure the political and financial support of international organizations.

In terms of financial management of the expected assets generated from the regional projects for Afghanistan, a special purpose fund could be established, and the money can be channeled through an independent body monitored by the UN. This independent body can then invest these funds through an off-budget mechanism on development projects from which the Afghan people can directly benefit and where the Taliban administration is not in direct control of the funds and its expenditure. This approach can change later, and the funds can be diverted to the Afghan financial institutions if the Taliban have fulfilled the conditions of the international community and proven themselves as an accountable and reliable administration.

It can be concluded that the ongoing inter-regional energy projects are of importance for political stability and economic development of the region between Central and South Asia and, therefore, a continuation of the projects is critical to achieve the expected long-term political and economic goals in the region. The management and oversight mechanism in regards to Afghanistan can help to have control over the Taliban and shall be led by the United Nations. This approach will ensure that the projects can be continued, the people of Afghanistan are not isolated and the Taliban are under regular monitoring by the international community measuring their actions towards the Afghan people, the region and the international community.

[1] Potential and Prospects of Regional Energy Trade in the South Asia Region (ESMP) published by the World Bank in 2008

[2] CASA-1000 HDVC line provides power only during five months of the year; therefore, the line can be used for the remaining months of the year for surplus supply from Central Asia to Pakistan

[3] AFG and PKA sections of the TAPI pipeline, with a capacity of 11 billion BCM/annum

[4] https://www.bbc.com/news/business-58325545

[5] https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/imf-suspends-afghanistans-access-fund-resources-over-lack-clarity-government-2021-08-18/

[6] Imports account for over 75 percent of Afghanistan’s currently available electricity, whereas Tajikistan, with 24 % (144 MW), is the second-largest supplier after Uzbekistan (Source: DABS, 2021)

[7] https://www.aljazeera.com/program/inside-story/2021/10/2/how-will-the-taliban-handle-its-dispute-with-tajikistan

Bibliography

Asian Development Bank (2014) ‘Central Asia- South Asia Regional Energy Trade’ [Power Point Presentation]. Available at: http://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/events/2014/Regional-Energy-Trade-Workshop/Presentation-Materials/009_104_209_Session2-1.pdf (Accessed: 17 August 2017)

Asian Development Bank (2020) Transaction Technical Assistance – Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan- India (TAPI) Gas Pipeline Project (Phase 1). Available at: https://www.adb.org/projects/52167-001/main (Accessed: 15 October 2021)

Eurasianet (2021a) ‘Uzbekistan foreign minister jets into Afghanistan for talks,’ Eurasianet, 07 October, Available at: https://eurasianet.org/uzbekistan-foreign-minister-jets-into-afghanistan-for-talks (Accessed: 08 October 2021)

Eurasianet (2021a) ‘Turkmenistan: Taliban of brothers’, Eurasianet, 07 October, Available at: https://eurasianet.org/turkmenistan-taliban-of-brothers

(Accessed: 08 October 2021)

European Union (2016) TAPI natural gas pipeline project- Boosting trade and remedying instability. Brussels: European Union.

Latifi, A.M. (2021) ‘Taliban still struggling for international recognition, AlJazeera English, 07 October, Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/10/7/taliban-afghanistan-international-recognition (Accessed: 11 October 2021)

Nichols, M., and Psaledaki, D. (2021) ‘Russia’s Lavrov says Taliban recognition ‘not on the table,’ Reuters, 25 September, Available at: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-lavrov-says-taliban-recognition-not-table-2021-09-25/ (Accessed: 05 October 2021)

NRP (2021) ‘With The Taliban’s Rise, India Sees A Renewed Threat In Kashmir,’ NRP, 14 September, Available at: https://www.npr.org/2021/09/14/1036877490/with-talibans-rise-india-sees-renewed-threat-in-kashmir (Accessed: 12 October 2021)

Pannier, B. (2018)’ Afghan TAPI Construction Kicks Off, But Pipeline Questions Still Unresolved,’ Radio Free Europe, 23 February, Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-tapi-pipeine-afghanistan-launch/29059433.html (Accessed: 10 October 2021)

Pannier, B. (2021) ‘Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan Open Channels with The Taliban, Radio Free Europe, 01 October, Available at: https://www.rferl.org/a/qishloq-ovozi-tapi-pipeine-afghanistan-launch/29059433.html (Accessed: 10 October 2021)

Singh, A., Jamash, T., Nepal, R. and Toman, M. (2015) Cross-Border Electricity Cooperation in South Asia. Washington: World Bank.

Sridharan, K. (2007) Regional Cooperation in South and Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies.

Watkins, A., Olsen, R., Mir, A. and Bateman, K. (2021) Taliban Seek Recognition But Offer Few Concessions to International Concerns. Washington: United States Institute of Peace.

World Bank (2008) Potential and Prospects for Regional Energy Trade in the South Asia Region. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/380071468306294151/pdf/462820ESM0bBox1egional1energy1trade.pdf (Accessed: 10 April 2017).

World Bank (2017) One South Asia. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/south-asia-regional-integration (23 August 2017).

World Food Programme (2021) Data Afghanistan. Available at: https://www.wfp.org/countries/afghanistan (Accessed: 10 October 2021)