Introduction

With the state collapse on 15th August and the subsequent taking over by the Taliban, Afghanistan once again looks into an uncertain future. The recent developments led to the breakdown of the civilian state institutions and the entire security sector and had devastating consequences for the country’s economy. The banking system is near to collapse, the inflation is soaring, and , people are desperate as most of them have lost their jobs and are short of cash.

This month, the UNDP announced that if the current political and economic crisis is not addressed; as much as 97 percent of the population will sink below the poverty line until mid-2022. In addition, Afghanistan is suffering from severe drought, with over half of the country is in an acute food security crisis.[1] (FEWS, 2021), which will worsen during the upcoming winter.

The international community has pledged over USD 1 billion as humanitarian assistance to the country in order to avoid a humanitarian disaster. However, the implementation process is still on a slow path and has to be expedited to bring the urgently needed aid to the beneficiaries.

The state-owned power utility Da Afghanistan Breshna Sherkat (DABS) still provides electricity to its customers. However, due to a lack of revenues and the daily increase of due payments, the utility will soon not be able to pay the due payments to the foreign and domestic power providers and will not be able to cover its operational costs. Thus, the risk of a complete collapse of the utility within the next weeks is imminent.

Therefore, it is essential to consider preventive measures that include the continuation of DABS’ operations and alternative options in case of a decrease of the available on-grid power.

The following blog starts by providing a background of the power sector of Afghanistan, then illustrates the current situation of the power sector, and concludes with a proposed emergency plan to rescue the power sector from collapse.

Background

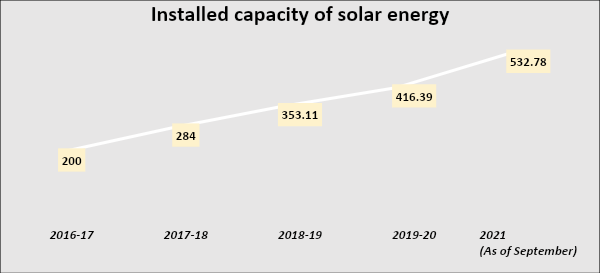

Afghanistan is a country that possesses vast resources for electricity generation from renewable sources such as hydro, solar, and wind. The country’s hydro generation potential is estimated at 23,000 MW, whereas the wind potential is 67,000 MW (Ministry of Energy and Water, 2015). With 300 sunny days per year (Ghalib, 2017), Afghanistan has excellent potential to generate a significant part of its electricity demand from solar energy.

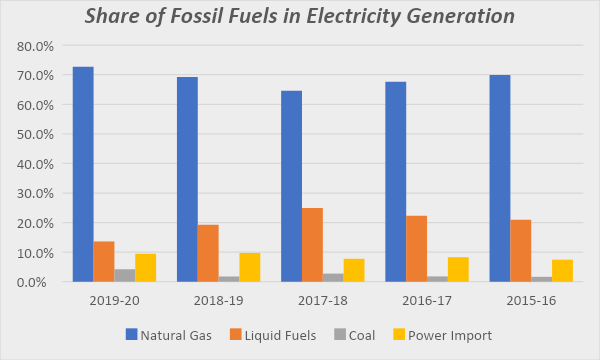

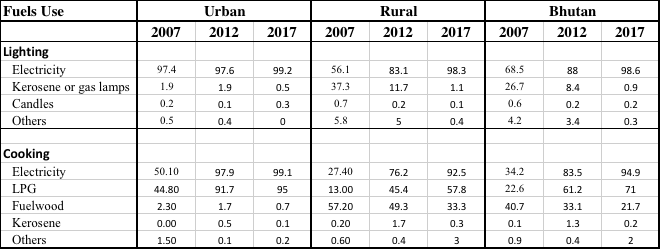

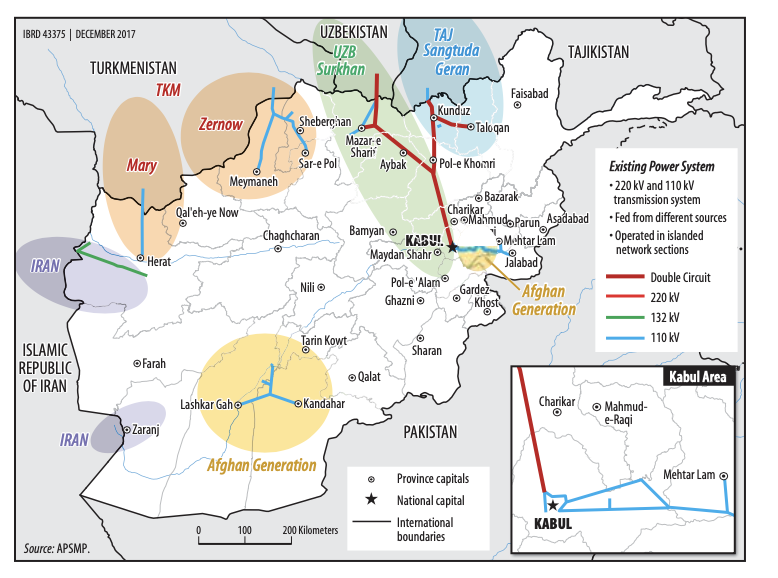

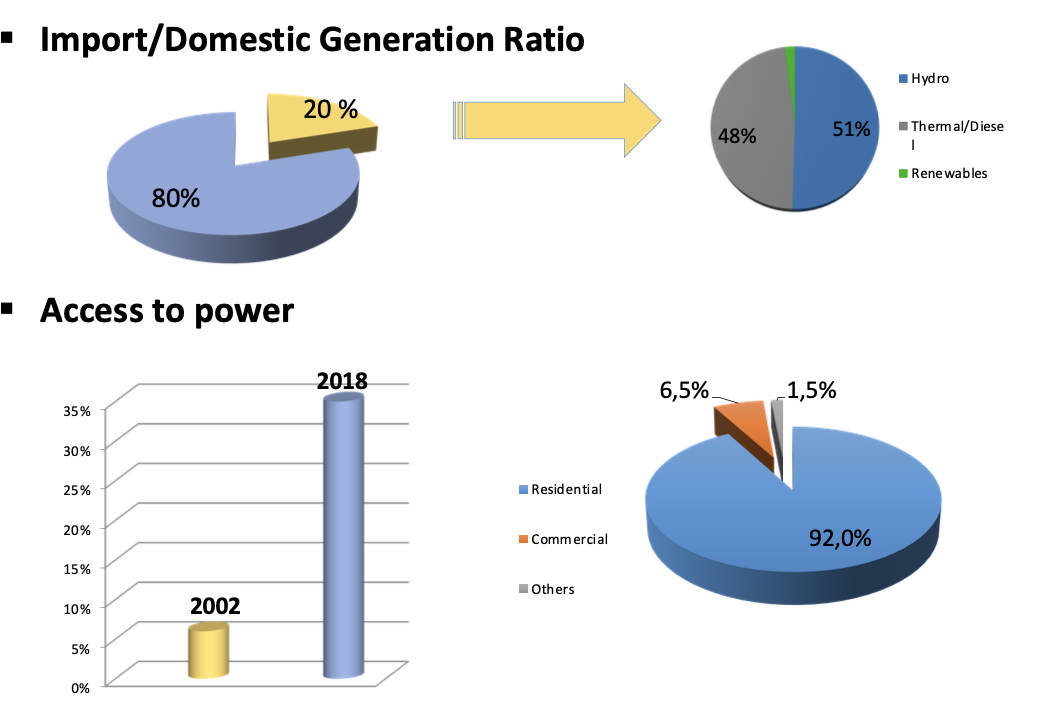

Despite the vast potential for domestic power generation, the country is importing more than 75 percent of its power from Central Asia and Iran (DABS, 2020). Around 20 percent is generated on Afghan soil, with hydropower as the premier source of generation.

In terms of institutional arrangements, the Afghan power sector was led by the Ministry of Energy and Water.[2] responsible for all activities on a policy level, whereas DABS was the state-owned power utility responsible for the supply of electricity to consumers and the operation and maintenance of generation, transmission, and distribution in the county. Despite the efforts of the international community and Afghan stakeholders, the third pillar that shall have been responsible for regulation purposes was never in place. The recent changes ordered by the former government led by Ashraf Ghani that dissolved the Ministry of Energy and Water and replaced this institution with two independent authorities was a step leading to further complications of the situation without tangible results in regards to clarity on roles & responsibilities and increase of accountability and transparency.

Figure 1: Afghanistan Grid System & Power Imports (Gencer et al., 2018)

Worth noting that with the collapse of the Ghani-led government and taking over of the country by Taliban, the two independent authorities- NAWARA and ESRA- have been replaced by the Ministry of Energy and Water.

Despite the progress made during the last two decades where the connection rate was increased from less than 5 percent to over 30 percent, the power sector of Afghanistan continued to suffer from challenges in this area . The main issue, besides the lack of robust and accountable institutions and operational inefficiencies (e.g., up to 45 percent losses[3] ) was the huge dependency of the country on imported electricity from neighboring countries, mainly Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Iran. According to DABS, still over 75 percent[4] of the electricity is still imported from neighboring countries, which costs Afghanistan over USD 280 million annually (Jahanmal, 2020).

Figure 2: Power Sector- Import/Domestic Ratio & Connection Rate (dated: 2018)

The reasons behind the decision for power imports rather than developing the vast domestic resources of the country go beyond the scope of this brief concept note and, therefore, will not be discussed further. However, one can clearly state that the lack of sufficient domestically generated electricity and the country’s huge dependency on imports was a main impediment to Afghanistan’s economic self-reliance.

The current situation, in particular in the light of the recent development in the country, has worsened the conditions of the power sector of Afghanistan.

Current situation of the power sector in Afghanistan

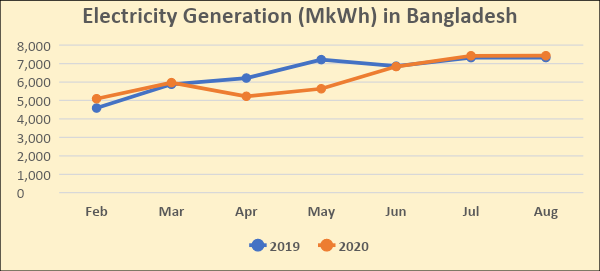

According to reliable sources from within DABS, the utility is on the verge of complete collapse if the international community does not provide the required financial means to maintain a basic level of operation of the utility. Current figures indicate that DABS’ due payments are at USD 85 million[5] whereas the total revenue collection as of 27th September is only USD 49 million- a deficit of USD 36 million. Considering the fact that DABS will not be able to collect any additional revenues in the upcoming months but still has to continue the supply of power, the number of the due payments will further increase.

If DABS cannot pay the power suppliers, the involved countries and the Independent Power Producers (IPPs) will most probably stop the supply of power to DABS and, depending on the contractual conditions, claim even additional compensations and penalties from the utility.

This situation would mean that the power utility has to stop operations due to a lack of financial means to purchase power, pay its personnel and cover its O&M costs. Moreover, the domestic generation of power provided by hydropower will also decrease during the winter months. Emergency operations through diesel generators and utilization of existing thermal power plants will be too costly and, considering the current financial situation of DABS, not a feasible option.

Consequently, not only will the Afghan people remain without light, but critical public services, such as the health and water supply sectors, will not be able to continue operations. If this situation occurs, it will not further deteriorate the catastrophic humanitarian situation but may also lead to an uncontrollable political destabilization of the country.

To avoid the mentioned collapse of the power sector of Afghanistan, urgent support is required. The focus shall be here on the continuation of power supply to critical public services, such as health and water supply, and the provision of financial support to DABS to pay its bills, personnel and maintain the existing power generation facilities and transmission & distribution networks.

Alternative options during the current emergency situation

Considering the criticality of the situation, it is of utmost importance to assess the acute crisis and provide a viable solution to avoid a complete collapse of the power sector.

To achieve this, it is crucial to prioritize the supply of public facilities, such as hospitals and water supply utilities, to ensure the delivery of these services to the people. This means that DABS has to adjust its operation and focus on providing electricity to critical public infrastructure.

For this, the utility shall also provide a realistic emergency plan that contemplates the emergency operation’s technical and financial/ commercial aspects.

Within the approach mentioned above, the supply of power to private customers shall not be neglected, and alternative supply options must be contemplated. A viable option during the emergency phase could be installing off-grid solar rooftop systems and supplying DC- solar home kits to the people. Whereas installing solar rooftop systems (0.1-1 kW) could be a viable solution for cities such as Kabul, the DC solar home kits could cover semi-urban and rural areas of the country.

Through this two-fold approach, DABS will continue to provide electricity to critical public services institutions , and satisfy its private customers’ electricity needs by providing off-grid solutions. The advantage of the off-grid solutions is that the current burden on DABS will be reduced, and the beneficiaries are also released from paying bills to the utility, which they anyhow cannot afford at the moment.

However, considering the current situation of the banking sector and the financial liabilities of DABS, the plan mentioned above is not implementable without the support of the international community. The international community does not recognize the current administration of the Taliban and, therefore, formal communication on a bilateral and multilateral level between the Taliban and the international community, including international financing institutions and bilateral donor agencies, is not possible at this stage.

Thus, the only viable option remains the pro-active engagement of the United Nations in the process. The United Nations shall commence its direct communication with DABS’ leadership and ask them to provide an emergency plan that considers the aforementioned aspects. Moreover, the United Nations could take the lead to discuss the current financial constraints of Afghanistan with the Central Asian countries and Iran and also the few Independent Power Producers and provide the required guarantees on the due payments to ensure the continuation of the power supply to the DABS’ network.

Furthermore, through its agencies such as UNDP, the UN could draft a distribution plan for the off-grid solutions and make the required arrangements to start the installation and distribution of the systems, respectively. The UNDP could seek cooperation with the World Bank-initiated program- Lighting Global- which has the experience and certified suppliers in Asia who could provide the tools.

Conclusion

The current situation of the power sector in Afghanistan is critical and requires the international community’s urgent attention. A possible collapse of the country’s power sector has enormous consequences for other public services and can also lead to the further deterioration of the volatile situation of the country.

To avoid the disastrous effects of such a collapse, it is therefore of utmost importance to that United Nations take the lead and draft in collaboration with the technical staff of DABS a comprehensive emergency power supply program that ensures the continuation of power supply to critical sectors, such as water supply and health. Moreover, the plan shall foresee the provision of off-grid solutions to private consumers and the provision of required financial guarantees to power suppliers (imports and IPPs) to ensure the continuation of the electricity supply by DABS.

[1] Famine Early Warning Systems Network- https://fews.net/central-asia/afghanistan

[2] In 2020, the Ministry of dissolved and two new independent authorities were established- National Water Regulatory Authority (NAWARA) and Energy Services Regulatory Authority (ESRA)

[3] Technical and commercial losses (Power Sector Masterplan, 2013, p. 3-14)

[4] The figure varies between 75 and 80 percent; Considering the seasonal variations in terms of domestic capacity and demand (summer vs. winter), 80 percent is to be a realistic figure

[5] Imports and Independent Power Producers (IPPs)

Bibliography

Ghalib, A. (2017) ‘Afghanistan’s Energy Sector Development Plans’ [Power Point Presentation]. Available at: https://www.ekonomi.gov.tr/portal/content/conn/UCM/uuid/dDocName:EK-236901;jsessionid=K-M8GZmdX0-bSKpv0O7NR8_CD-VSxKcz_UZZqpyDWSK6Oq9YaU-M!3487174 (Accessed: 20th September 2017).

Gencer, D., Irving, J., Meier, P., Spencer, R. and Wnuk, C. (2018) Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Energy Security Trade-Offs under High Uncertainty: Resolving Afghanistan’s Power Sector Development Dilemma. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/136801488956292409/Islamic-Republic-of-Afghanistan-energy-security-trade-offs-under-high-uncertainty-resolving-Afghanistans-power-sector-development-dilemma (Accessed: 29th September 2021).

Jahanmal, Z. (2020)’ Afghanistan Annually Pays $280 million for Imported Power, Tolonews, 30th August, Available at: https://tolonews.com/business/afghanistan-annually-pays-280m-imported-power (Accessed: 30th September 2021).

Ministry of Energy and Water (2015) Renewable Energy Policy. Available at: http://www.red-mew.gov.af/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Afghanistan-Renewable-Energy-Policy-English-and-Dari.pdf (11th June 2017).