Poor Air Quality is a burning issue in many of the countries of South Asia. India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh do not meet air quality standards set by the World Health Organisation. One of the key reasons for poor air quality in the region is largely due to a predominance of coal-fired power plants and increasing vehicular pollution. The Energy Transition Platform intends to build a constituency of stakeholders across the region to advocate for more stringent & cleaner emission norms and enhance knowledge sharing amongst member countries to enable a faster energy transition.

Energy Poverty continues to be a dominant issue in most countries of South Asia.Clean, affordable, and reliable energy supply continues to be in short supply, particularly in Nepal, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh.

The Energy Transition Platform envisages 100% clean, affordable reliable energy supply in all countries of South Asia.

Per Capita Electricity Consumption as per latest year available

The total capacity of non-fossil fuel in South Asia for 2023 stood at 41.26% and has seen a steady increase over the past few years.The percentage of share of non-fossil fuels in these countries ranges from 99.64 % (Bhutan) to 4.61% (Bangladesh).

The Energy Transition Platform (ETP) recognizes the effort of the region on its renewable energy targets. However, the platform wishes the region to aspire to an increase in the renewable energy targets. South Asia region is home to almost a quarter of the world’s population and countries in this region are on the path of rapid development and economic growth. With the need to keep global temperature from rising above 1.5°C, a rapid energy transition is required here. ETP intends to build a constituency of stakeholders across the region for a fossil-free vision through policy advocacy and dialogue.

Total Fossil Fuels and Total Non-Fossil Fuels (MW)

Reporting periods:Financial years for South Asian countries vary from 1st April to 31st March, 1st July to 30th June, 16th July to 15th July, 1st January to 31st December.In order to ensure uniformity in the data representation data has been presented as a calendar year for all countries.For those countries that do not have a 1st January to 31st December reporting period, apportionment has been carried out.Monthly data has been corroborated wherever available.

Pakistan’s energy sector is heavily reliant on imported fossil fuels, which heightens its exposure to rising costs and supply chain disruptions, directly affecting financial sustainability. This dependency also amplifies Pakistan’s vulnerability to climate-related risks, as fossil fuels dominate the energy mix with a share of 59.4 percent. Ranked among the most climate-vulnerable nations globally, Pakistan faces urgent pressure to transition toward an indigenous renewable energy source such as solar, wind, biomass, and micro-hydro projects that could enhance energy security and offer Pakistan a more resilient and low-carbon future. Recognizing this, the government has set ambitious goals to transition the country towards clean energy. Pakistan’s ‘Alternative and Renewable Energy Policy 2019’ aims to shift the energy mix to 30% renewable sources by 2030. The policy encourages both local and international investment, setting the stage for innovation and a shift towards greener, more sustainable energy production. Currently renewable sources contribute 6.8 percent of the energy mix, while hydel and nuclear energy adding 25.4 percent and 8.4 percent, respectively.

On-Grid Renewable Potential: Pioneering Projects and Policy Actions

Pakistan is taking several decisive steps to develop its on-grid renewable energy potential. In 2023, the country launched its first round of competitive bidding for the ‘Solar Fast Track’ program, aiming to install 10,000 MW of solar power. Solar energy potential is significant across the country, with Western Pakistan enjoying an average annual Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) of 2330 kWh/m², among the highest globally. The government is currently establishing three solar power projects (each 50 MW) in Sukkur. In addition, as of March 2024, net metering based solar installations stand at 117,807 with a cumulative capacity of 1,822 MW. The number of active certified installers has surpassed 400. The government is also working on solarization of public sector buildings. To make sure that Pakistan has enough human resource to install and maintain solar projects, the government is training 500 technicians at various training centers.

In addition to solar, Pakistan’s wind energy potential is notable, with an estimated 346 GW capacity. The government has already established a wind energy corridor along the southern coastal regions of Sindh and Balochistan. The Gharo-Jhimpir wind corridor in Sindh alone could provide 11 GW of energy. The country’s latest Integrated Generation Capacity Expansion Plan (IGCEP) 2022-2031 outlines a target of 4,928 MW of wind capacity by 2031 which would an increase the percentage of wind energy from 4 percent to 10 percent in the total energy mix. Considering rapidly falling equipment costs and improved procurement strategies, wind tariffs have dropped to as low as 3.5 US cents/kWh, encouraging further development in this area. Currently, three projects with a cumulative generation capacity of 108 MW are under process.

Biomass also offers considerable potential, particularly in the agricultural sector. The country’s sugar mills, for example, could generate up to 1,844 MW annually from bagasse. By harnessing bio-waste from both agricultural and municipal sources, Pakistan could further enhance its renewable energy portfolio, reduce waste, and contribute to a circular economy.

Off-Grid Renewable Solutions: Powering the Remote and Rural

While on-grid projects are gaining momentum, the need for off-grid solutions is equally pressing, especially in rural and underserved areas. In many remote regions, grid access remains limited, and reliability issues are common. For such areas, off-grid solutions offer an immediate path to electrification and improved quality of life. The deployment of Solar Home Systems (SHS), mini-grids, Micro Hydel Power Projects (MHPP), and small-scale biogas plants are already providing renewable power to areas beyond the reach of the national grid. However, these are mostly at a nascent stage.

Micro hydropower, in particular, has been effective in reaching remote areas, especially in the northern regions where up to 30 percent of the population lacks grid access. These systems offer a reliable, cost-effective solution, with minimal land requirements and ease of community-based operation and maintenance. Solar mini-grids are also gaining traction as viable off-grid solutions, with an estimated 1,015 potential mini-grid sites across the country. A World Bank study projects that connecting approximately 4 million consumers to mini-grids by 2030 could bring Pakistan closer to universal electrification at a low cost. Similarly, the development sector is promoting the use of small-scale biogas plants in underserved rural communities. However, it is important to quantify the exact potential of off-grid solutions, implement a fair licensing system, build expertise of communities and technicians in installing and maintaining off-grid solutions, and encourage private sector to provide cost-effective and efficient solutions.

The Way Forward: Scaling Renewables for a Sustainable Energy Future

Transitioning to a renewable energy future for Pakistan requires a comprehensive, multi-pronged approach. Prioritizing investment in solar, wind, and biomass infrastructure while expanding off-grid renewable solutions will be essential. The government’s focus on competitive bidding, transparent policies, and international partnerships can support sustainable growth in this sector. Additionally, enhancing information dissemination and public-private cooperation for off-grid projects will attract further investment and expertise. The development sector too can play a vital role in supporting small-scale off-grid solutions in underserved areas. Some progress is already being made support small-scale farmers and rural communities.

Pakistan has great potential for installing renewable power sources. By capitalizing on its solar irradiance, wind corridors, and biomass potential, the country can create an energy system that supports economic growth, social development, and environmental sustainability. Embracing this renewable pathway promises not only to decarbonize the power sector but also to shape a future where energy security, economic resilience, and climate responsibility go hand in hand.

Date Sources:

The following blog aims to provide an overview of the historical background of regional Cooperation in South Asia’s electricity sector, the current status, including challenges and drivers, and the prospects of cross-border cooperation in the region, considering political, economic, and climate change-related aspects.

2. Background

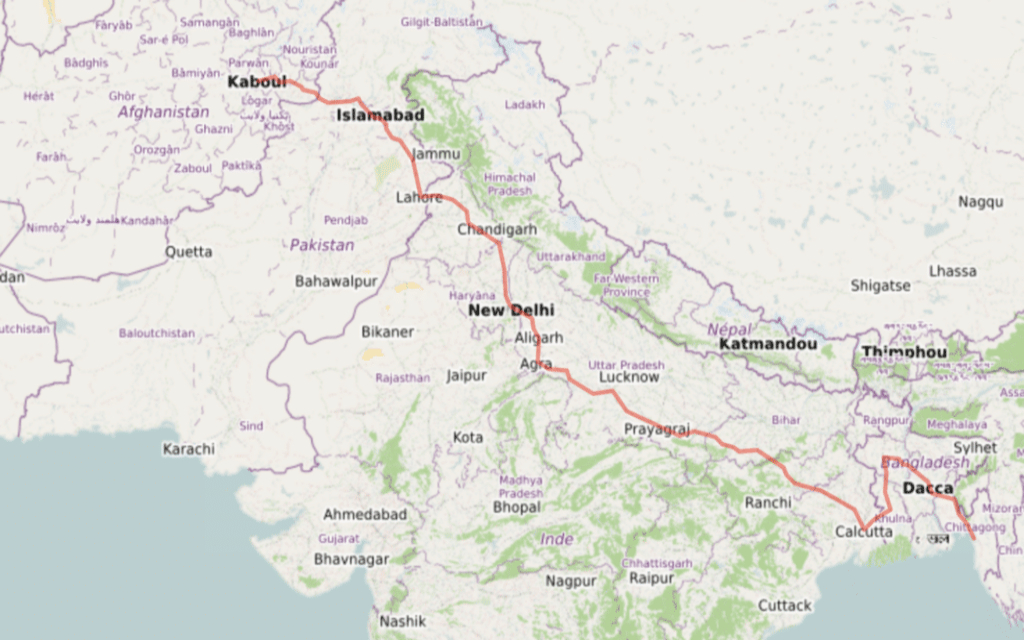

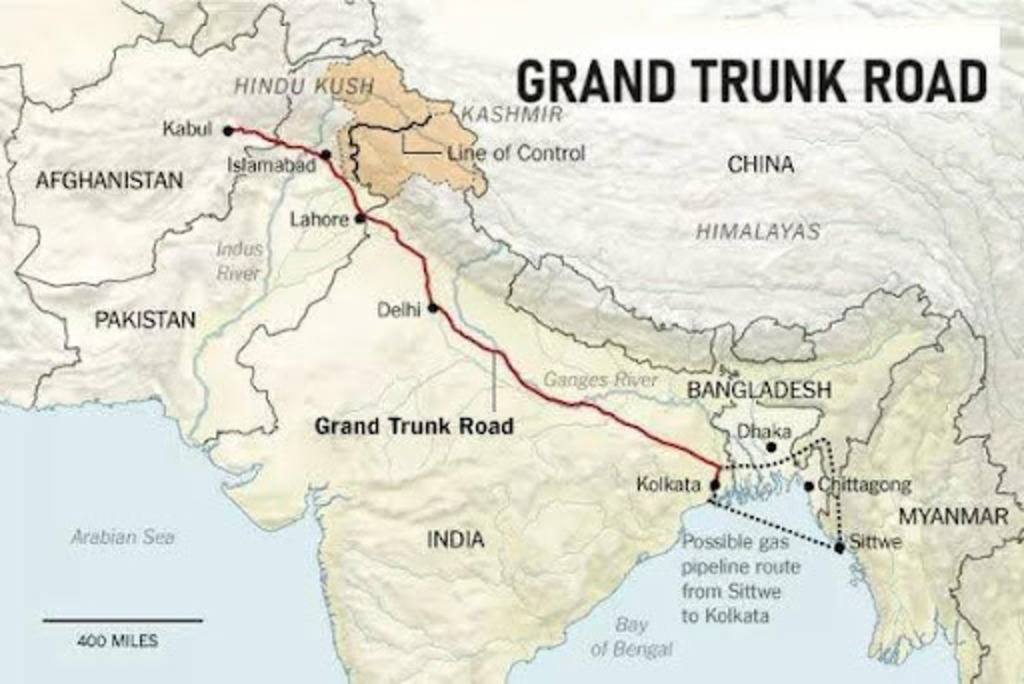

Looking at history, regional cooperation is not an unknown phenomenon. The ancient Silk Road connected East and West Asia, facilitated trade, and benefited the countries1. The “Sarak-e-Azam,” built during the 16th century by the Afghan Sultan Sher Shah Suri, is yet another example of connectivity in the region. It connected the cities of Agra and Sasaram in the first stage; later, the road was extended to Kabul. Today, the road is known as the “Grand Trunk Road,” connecting India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Unfortunately, colonialization and rivalries between superpowers in the last three centuries, security concerns, and post-colonial cross-border conflicts among the countries during the last decades have hampered connectivity in the region.

In the 20th century, the first institutionalized approach to facilitate regional Cooperation in South Asia started with the establishing the South Asian Cooperation for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1985 Dhaka, Bangladesh. Despite SAARC’s existence for decades, South Asia is still one of the least integrated regions in the world, where the share of intra-regional trade accounts for only five percent3 of the region’s total trade. Labeled as a study-driven regional institution, many scholars and policymakers question SAARC’s capacity to be an effective platform to foster regional cooperation.

Regional cooperation in the energy sector /cross-border electricity trade (CBET) in South Asia was, until recently, limited to bilateral cooperation between the countries, mainly India-Bhutan, India-Bangladesh, and India-Nepal. Thus, the cross-border trade is currently limited to the BBIN 4sub-region of South Asia.

The CASA-1000 high-voltage transmission line from Central Asia is the first major interregional power project to facilitate electricity transmission between Afghanistan and Pakistan. For the time being, the extension of this line to other South Asian countries, such as India, is not contemplated.

The following will discuss the current status of CBET in South Asia, followed by an analysis of the main challenges and drivers and the prospects of CBET in the region.

3. Current Status of CBET in South Asia

As mentioned, CBET in South Asia is currently limited to bilateral trade between the BBIN countries and cannot be expanded beyond the sub-region. About 700 MW of electricity is traded between India and Nepal via different transmission routes. Bangladesh imports 1,160 MW from India, while Bhutan exports approximately 2,325 MW to India.5India and Sri Lanka lack a direct electricity connection, but there are plans for cross-border connectivity via undersea cables or overhead transmission lines.

In the financial year (FY) 2021-22, around 16,820 GWh of electricity was traded among BBIN countries. The electricity exchange within the BBIN nations has increased nearly 2.2 times since 2014, totaling 7,705 GWh. In FY 2021-22, India imported 7,597 GWh from Bhutan and exported 7,302 GWh to Bangladesh and 1,921 GWh to Nepal6. For the FY 2022-23, the net power transaction in the BBIN region was at 15,160 GWh7.

Table 1 below summarizes the CBET capacity and electricity trade volume within the BBIN sub-region.

| Particulars | Quantum (MW) | Electricity Transacted (GWh) in FY22 |

|---|---|---|

| India-Bangladesh | 1,160 | 7,302 (Export from India) |

| India-Nepal | ~ 700 | 1,921 (Bi-directional) |

| India-Bhutan | 2,325 | 7,597 (Bi-directional) |

Although current trade is limited to a bilateral level, several initiatives for trilateral trade in the BBIN subregion are also underway. One such initiative is the export of electricity from the 900 MW Upper Karnali hydropower plant (HPP) in Nepal to Bangladesh—a project developed by the Indian private developer GMR. Another project is the 1,125 MW Dorjiling HPP in Bhutan, aiming to deliver power to Bangladesh via India.

The first tangible initiative within the BBIN sub-region of South Asia to excel in the current bilateral-to-trilateral trade has been concluded recently with the signing of an MoU between Nepal, India, and Bangladesh. Nepal will export its surplus power from June to November via India to Bangladesh, whereas during the first phase, the trade is limited to 50 MW9.

Considering the political tensions between India and Pakistan, there will be no noticeable collaboration between the two countries in the near future. This situation is affecting not only the cooperation between the two countries but also disrupting connectivity on a regional level.

In addition, the political situation in Afghanistan since August 2021 is another serious obstacle to enhanced and seamless power trade in the region. Despite the country’s insecurity, Afghanistan was considered, during the last two decades, the key linkage between Central and South Asia, with major regional projects, such as the CASA-1000 transmission line, Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan Transmission Line (TAP), and TAPI.10 gas pipeline planned to be routed through Afghanistan. It was aimed that these regional energy projects would enhance energy trade and have a spill-over effect on other economic sectors in Central and South Asia. Although the World Bank announced in February 2024 the resumption of the CASA-100011 project The future of TAPI and TAP still needs to be clarified. Besides economic factors, geopolitical considerations will determine the future of these regional projects.

4. Drivers and challenges for CBET in South Asia

In addition to the aforementioned geopolitical rivalries in the region, various challenges and drivers (see Table 2 below) are decisive for Regional Cooperation in the power sector in South Asia.

The political, economic, and systemic asymmetry vis-a-vis India is a clear bottleneck. This multi-dimensional imbalance causes, particularly in the region’s smaller countries, hesitance to foster cooperation. The imbalance is also visible in the vast differences in quantity and quality of required electricity infrastructure, which not only makes an enhanced CBET difficult but also leads to serious challenges in attracting foreign investment in generation and transmission. Moreover, the need for more policy and regulatory frameworks in many countries on a national level is another challenge to seamless cooperation. For example, India is the only country in the region with dedicated CBET guidelines; no other country has yet developed a similar guideline that outlines the framework for regional electricity cooperation. Finally, the lack of a functioning regional institution that fosters collaboration, coordination, and trust and is positioned to draft an accepted and holistic decision-making process is another major obstacle for CBET in the region.

However, despite the existing challenges, many factors have been recognized by the countries as enablers/drivers to overcome the current impediment. This is particularly valid for the BBIN sub-region, considering the development since 2014, as indicated in the previous section.

The recent conflict in Ukraine has once again reminded the regional countries of their huge dependency on fossil fuel imports and its impact on the countries’ economies. Therefore, enhanced regional cooperation through electrification of the energy sector improves energy security and supports the countries in achieving the envisaged NDC targets. Regional cooperation is an important pillar, considering the complementarity potential in terms of resources and their demand in the region. Besides the required policy and regulatory framework, an essential pillar for seamless cooperation is upgrading and expanding the in-country transmission infrastructure, followed by expanding cross-border interconnection. A coordinated approach covering policy, regulatory, and infrastructure-related aspects would encourage international development partners and private investors to invest in the required infrastructure. The existing bilateral trade from the region and the experience from other regions can be utilized to improve current cooperation, even if only the BBIN countries are involved at this stage.

Considering India’s preference toward BIMSTEC, it would be realistic to commence the enhanced cooperation within this regional institution; however, it should also be noted that long-term isolation of Pakistan and Afghanistan would have not only political implications but would also limit the economic opportunities that regional Cooperation offer through connectivity to other regions, such as Central Asia. Therefore, it is essential to consider the most viable option for the time being without neglecting the implication of a possible isolation of Pakistan and Afghanistan. As BIMSTEC offers opportunities for Cooperation with Southeast Asian countries, the possible extension of Cooperation to Pakistan and Afghanistan will pave the way for collaboration with another important region- Central Asia.

| Enablers/ Drivers | Challenges |

|---|---|

| • Achieving energy security by reducing current dependency on fossil fuel imports and accelerating electrification of the remotest areas | • Pakistan-India political tensions are the central impediment towards seamless CBET in the region |

| • Meeting NDC targets by trading surplus clean energy and exploiting the untapped potential of renewable energy using domestic and cross-border transmission lines | • Political, economic, and systemic power asymmetry vis a vis India is perceived as a bottleneck for enhanced regional cooperation |

| • Increased number of cross-border transmission lines and established mechanisms | • Inadequate/ poor electricity infrastructure within each country and across borders for a seamless two-way flow of electricity and challenges in attracting foreign and private investments for building new hydropower/ RE projects and transmission lines |

| • Strong experience and ecosystem of bilateral trade and access to international best practices through the initiatives of development partners | • Inadequate policy and regulatory framework on a national level to facilitate enhanced CBET |

| • Regional institutions, serve as a possible option to anchor regional CBET initiatives | • Lack of dedicated engagement modality or institutional platform at the regional level to foster cooperation, coordination, trust, and a holistic decision-making process |

| • Electricity cooperation provides spill-over benefits and boosts cooperation in other sectors |

5. Prospects of enhanced CBET in South Asia and conclusion

As stated, the political tensions between Pakistan and India are considered the main impediment to enhanced regional electricity cooperation in South Asia. Therefore, cooperation between these two countries in a critical sector, such as the electricity sector, is not realistic for now. This situation hinders collaboration between these two countries and disconnects Afghanistan from regional Cooperation in South Asia. In addition, the existing disconnect between these countries impedes inter-regional Cooperation between South Asia and the energy-rich Central Asia, which would facilitate power trade and open up the path to collaboration in other key economic sectors.

Considering the current stagnation on a regional level, it can be concluded that the prospects of cross-border cooperation in the axis between Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India are not very promising until the leaderships of Pakistan and India resolve the existing political issues.

On the other side, the recent positive developments within the BBIN countries, focusing on an economic rather than political agenda, indicate that cross-border Cooperation in South Asia is not impossible. India, the key regional player in the sub-region, is pursuing the enhancement of cooperation and has shown a willingness to facilitate trilateral power trade between the regional countries. The MoU between Nepal, India, and Bangladesh on the transmission of power from Nepal to Bangladesh via India can serve as the basis for future multilateral electricity cooperation in the sub-region. Moreover, the countries view CBET as an opportunity to enhance energy security and expedite the process of clean energy transition in their countries.

The establishment of the BIMSTEC12 Energy Centre in Banglore, India, indicates India’s commitment to enhancing regional power cooperation. India favors BIMSTEC due to its geoeconomics focus and alignment with the country’s Act East policy.

India’s active engagement in the BIMSTEC regional platform, which also includes the Southeast Asian countries of Myanmar and Thailand, further reduces the chances of SAARC playing a pivotal role in enhancing regional electricity cooperation in South Asia. This, in turn, confirms the statement above that in the near future, regional cooperation will be limited to the BBIN sub-region and will not expand to Pakistan and Afghanistan- a situation which could be considered as an opportunity by other players, such as China, to achieve its geo-economic objectives in the broader region. The ongoing discussion13 the expansion of the China-Pakistan-Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a clear sign of China’s willingness to expand its influence in this belt, which might further reduce the prospects of an interconnected South Asia.

Therefore, it is of utmost importance to pursue enhancing cooperation in the BBIN sub-region without neglecting the importance of including Pakistan and Afghanistan in the regional framework in the long-term. This is a challenging task, but the only option is to facilitate long-term peace, prosperity, economic development, and a just green transition in the region through the creation of interdependency, where each country views regional cooperation as an opportunity rather than a burden.

1The Silk Road: Bridging Middle East and Asia

2 https://aisrs.org/31/the-grand-trunk-road-gt-road-a-historical-highway-of-harmony-and-heritage

3 https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/south-asia-regional integration/trade#:~:text=Intraregional%20trade%20accounts%20for%20barely,of%20at%20least%20%2467%20billion.

4 Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal

5 USAID-SARI/EI, Role of Cross Border Electricity Trade in Enabling the Renewable Energy Deployment & Integration in India/ South Asia Region, July 2022.

6 POSOCO Monthly Reports of March 2021 and March 2022, https://posoco.in/reports/monthly-reports/

7 POSOCO Monthly Report of March 2023, https://posoco.in/reports/monthly-reports/monthly-reports-2022-23/

8 POSOCO Monthly Reports of March 2021 and March 2022, https://posoco.in/reports/monthly-reports/; USAID-SARI/EI, Role of Cross Border Electricity Trade in Enabling the Renewable Energy Deployment & Integration in India/ South Asia Region, July 2022

9 https://indianexpress.com/article/news-today/nepal-india-bangladesh-agreement-cross-border-electricity-trade-9602203/

10 Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India

11 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/02/15/world-bank-group-announces-next-phase-of-support-for-people-of-afghanistan

12 Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation

13 https://www.voanews.com/a/extension-of-china-pakistan-corridor-to-afghanistan-presents-challenges-/7178387.html

Just Energy Transition: Bangladesh’s step towards transition to renewable energy

Background:

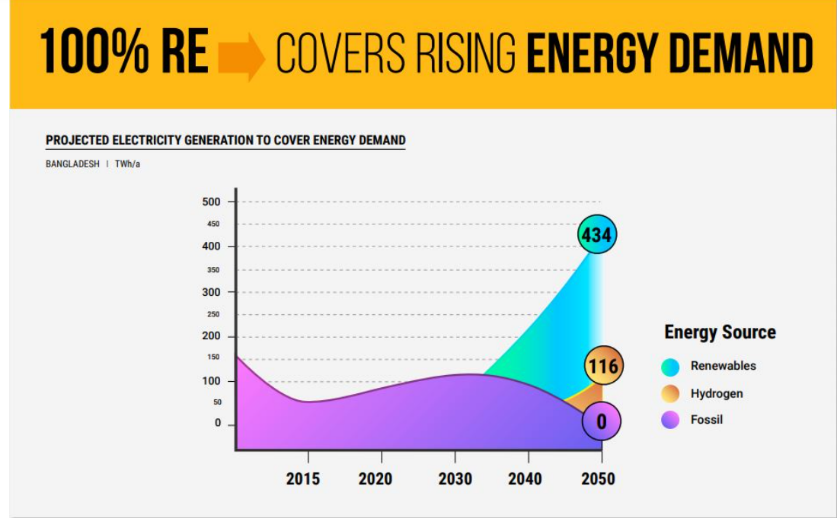

Bangladesh is at a pivotal moment in its energy journey. As the nation emerges from the 2022 power crisis, new opportunities are on the horizon to reshape its energy landscape. With a bold target to generate 40% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2040, the country is positioned to take significant strides toward a cleaner and more resilient energy future. However, balancing the move toward renewables while securing long-term LNG contracts will be key to ensuring a stable transition. Accelerating the shift to sustainable energy will help safeguard the power grid against potential disruptions and unlock economic growth.

The challenges ahead are substantial, driven by rapid population growth, urbanization, and industrial expansion. With near-universal electrification, Bangladesh’s power needs are growing, particularly in the ready-made garments sector, which contributes over 10% of the GDP and nearly 80% of exports. Diversifying the energy mix is now more crucial than ever to maintain momentum in economic development.

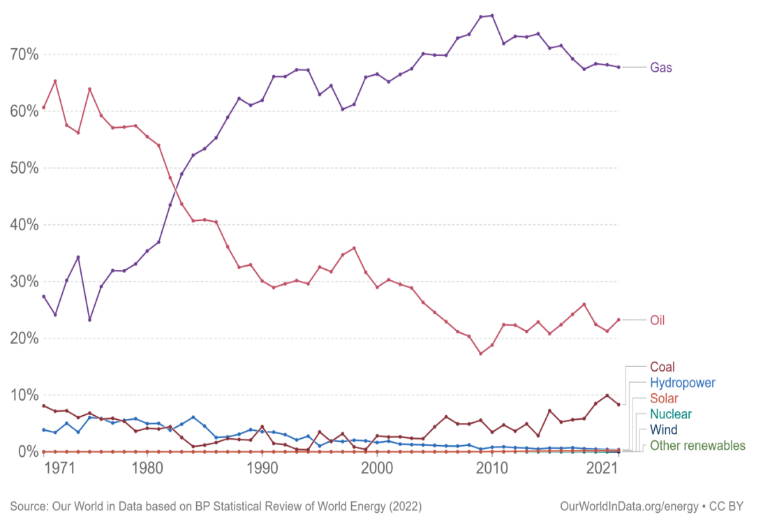

In 2021, over 99% of the country’s energy came from fossil fuels—primarily natural gas, oil, diesel, and coal—with natural gas alone accounting for around 67% of the supply, of which 26% was imported. This reliance has been instrumental in reaching electrification milestones, yet it also highlights the need for a more balanced energy strategy.

The shift from relying solely on domestic resources to embracing a diversified energy mix—including imports and renewables—presents an opportunity to enhance energy security, autonomy, and price stability. By accelerating the adoption of renewable energy, Bangladesh can build a more resilient grid that supports long-term economic growth, meets evolving energy demands, and positions itself as a leader in sustainable development.

Renewable Energy Potential:

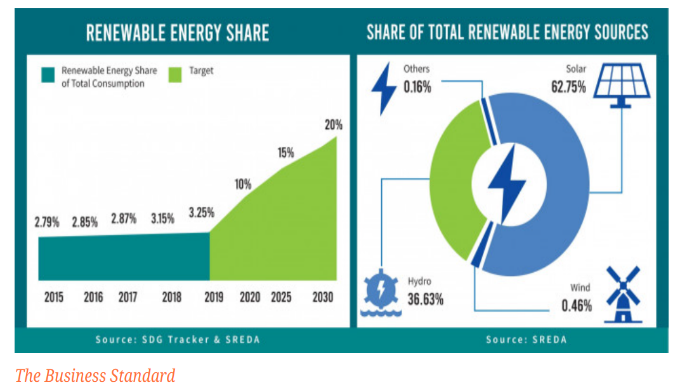

Bangladesh holds significant potential for renewable energy development, with solar, wind, and biomass resources offering promising prospects. The government has set ambitious targets to achieve 40% of its energy generation from renewable sources by 2041, a goal that is essential given the country’s rapidly growing energy demands and the need to reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Currently, solar power contributes approximately 4.5% to the total installed capacity, generating around 1,183 MW from various projects. With an estimated potential of 50,174 MW, solar energy could meet nearly 80% of Bangladesh’s projected energy demand by 2041. The draft National Solar Energy Action Plan aims for around 41 GW of solar power by that year.

Wind energy also presents a substantial opportunity, particularly in Bangladesh’s coastal regions, which offer favorable conditions for wind power generation. The potential wind capacity is estimated to be as high as 30,000 MW, with average wind speeds ranging from 5 to 8 m/s—ideal for turbine operation. Additionally, biomass remains a viable option for renewable energy, though its expansion is limited by competing demands for agricultural waste. Innovations such as biogasification could improve biomass utilization while ensuring sustainability.

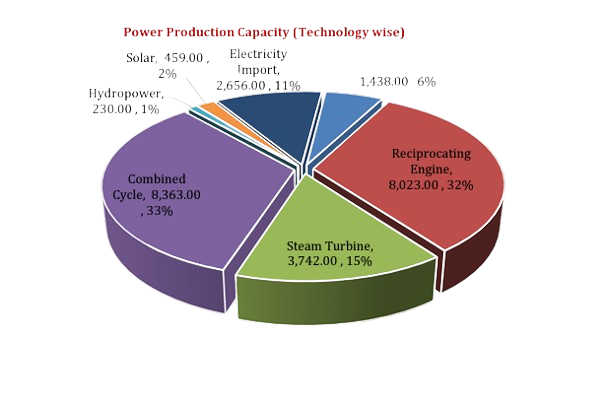

As of the end of 2021, Bangladesh’s total installed power capacity exceeded 29 GW, which included nearly 16 GW of oil-fired and 11 GW of gas-fired power. Renewable energy remained marginal, with only 230 MW from hydropower and 329 MW from solar. However, by 2022, renewable capacity had surpassed 950 MW. Under the updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) from August 2021, Bangladesh aims to achieve 4.1 GW of renewable capacity by 2030, including 2.3 GW of solar. The country also plans to expand its nuclear capacity, targeting up to 7 GW by 2041, with two 1.2 GW reactors at the Rooppur nuclear plant expected to be operational by 2024, and another nuclear facility under consideration.

Despite these plans, current renewable energy targets fall short of their potential. The Integrated Energy and Power Master Plan from 2023 outlines a goal of 18% clean energy by 2030 and 40% by 2041. While these figures may seem ambitious, they include controversial technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), ammonia, and hydrogen—which, despite being fossil fuel-based, are counted within the clean energy targets. In reality, only 5.7% of the 18% clean energy target by 2030 will come from renewables, rising to 8.8% of the 40% target by 2041. Currently, renewables make up just 2% of the national energy mix.

To meet its solar targets, Bangladesh plans to deploy the following:

- 16 GW through solar hubs

- 4 GW via electric utilities

- 5 GW by private developers

- 2.5 GW for irrigation pumps

- 12 GW from rooftop installations

However, scaling up solar energy faces several challenges, particularly the scarcity of land. Although Bangladesh’s tropical climate is suitable for solar, large-scale installations are hampered by limited available land. Agricultural land is prioritized for food production, and strict regulations prohibit its use for solar projects, complicating the identification of suitable sites due to fragmentation and competing land needs. Even when viable locations are found, land acquisition can be delayed by disputes and bureaucratic hurdles.

Furthermore, establishing solar power plants requires navigating a complex regulatory environment, involving up to 38 different licenses and certificates. This cumbersome process can discourage investors and slow project implementation. Financing solar projects is also challenging, as the initial investment is substantial and local financial institutions often do not offer favorable terms.

Integrating solar energy into the existing grid poses additional difficulties. The national power grid struggles with frequent outages and voltage fluctuations, which complicates the incorporation of intermittent solar power. Additionally, solar energy production varies due to changes in sunlight throughout the day and across seasons, necessitating advanced grid management and energy storage solutions to ensure a reliable power supply.

The challenges of establishing large-scale solar plants in Bangladesh have led the government to promote rooftop solar installations as a viable alternative for renewable energy transition. This strategy leverages the abundant rooftop space available in urban and industrial areas, addressing land scarcity while contributing to the country’s renewable energy goals. Rooftops of residential, commercial, and industrial buildings can be utilized without requiring additional land, making it an efficient use of space in a densely populated country. The government has introduced a net metering system, allowing users to connect their rooftop solar systems to the national grid. This enables them to sell excess power back to the grid, providing financial incentives and reducing electricity costs. The rapid installation of rooftop solar systems could significantly reduce carbon emissions. For instance, installing 2,000 MW of rooftop solar could potentially decrease CO2 emissions by about 15 million tonnes from 2023 to 2030, supporting Bangladesh’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under international climate agreements. Grameen Shakti as a pioneer of solar system installation has installed more than 350 solar roof top system both on Grid and Off grid which helped to reduce more than 11500 metric ton of carbon emission in the country. This is a step toward a just energy transition.

Just energy Transition:

A just energy transition refers to the process of shifting from fossil fuel-based energy systems to renewable energy sources in a manner that is fair, inclusive, and equitable for all stakeholders involved. It emphasizes:

- Social Equity: Ensuring that the benefits and costs of the transition are distributed fairly, particularly for marginalized and vulnerable communities.

- Decent Work Opportunities: Creating sustainable jobs in the renewable energy sector while protecting the livelihoods of those affected by the transition away from fossil fuels.

- Community Engagement: Involving local communities in decision-making processes to ensure their needs and voices are prioritized.

- Environmental Sustainability: Promoting clean, resilient energy systems that contribute to climate goals without exacerbating social inequalities.

Bangladesh’s Path Towards a Just Energy Transition

Bangladesh is making considerable progress toward a just energy transition, emphasizing climate resilience, sustainable energy development, and inclusivity in its policies and initiatives. This shift towards clean energy is not only addressing the country’s rising energy demands but also creating new opportunities for sustainable economic growth and gender equality.

Energy Landscape and Renewable Energy Development

Bangladesh currently boasts an installed energy capacity of 26,025 MW, with renewable energy sources contributing 1,201.85 MW. This includes 259 MW connected to the national grid and 418 MW generated off-grid. Although renewable energy represents a modest share of the total energy mix, solar energy plays a vital role, especially through decentralized systems such as Solar Home Systems (SHS), which have provided electricity to approximately 20 million people. The SHS initiative is one of the fastest-growing solar programs in the world, with over 6 million systems installed in off-grid areas.

The country aims to provide universal electricity access, and as of 2023, approximately 85% of the population has access to electricity, up from just 20% in 2000. However, around 40% still lack reliable electricity access, particularly in rural areas. To bridge this gap, the government has been expanding renewable energy projects, including a target to install 10,000 solar irrigation pumps by 2027 to support sustainable agricultural practices. Currently, around 1,515 solar pumps with a total capacity of 40 MWp are operational.

Challenges in the Transition

The journey toward a just energy transition involves addressing challenges such as scaling renewable energy projects, integrating them into the existing power grid, and replacing traditional energy sources like diesel-operated water pumps, which still number around 1.34 million and irrigate 3.4 million hectares of land. These pumps are costly and environmentally harmful due to fluctuating fuel prices and emissions. Shifting to solar-powered solutions can alleviate these concerns and further support the nation’s clean energy ambitions.

Employment Growth in the Clean Energy Sector

Bangladesh’s clean energy transition is creating sustainable employment opportunities. From 2011 to 2016, the solar sector experienced an annual job growth rate of 18.5%, significantly outpacing the national average of 1.9%. The workforce expanded from 60,000 to 140,000 during this period, showcasing the sector’s potential for generating sustainable livelihoods. The expansion of renewable energy projects is likely to continue driving job creation as the country scales its clean energy capacity.

Gender Inclusion in the Energy Sector

Women’s inclusion in the energy sector is critical to ensuring a just transition. In Bangladesh, women make up only 10% of the energy workforce, compared to the global average of 32% in the renewable energy sector. Closing this gender gap is essential for achieving a more equitable transition. Studies, such as one by McKinsey & Company, have shown that companies with greater gender diversity on executive teams are 21% more likely to experience above-average profitability. This underscores the economic benefits of including women in decision-making roles within the energy industry.

Grameen Shakti’s Role in Women’s Empowerment

Grameen Shakti is actively working to bridge the gender gap through initiatives such as capacity-building training under the WePOWER project. It has trained around 100 women annually, focusing on renewable energy knowledge and technical skills. These programs not only enhance women’s understanding of clean energy technologies but also empower them to become technicians capable of independently addressing electrical issues in their communities. Grameen Shakti’s training of female technicians and other capacity-building programs are vital steps toward increasing the installation of SHS and promoting the acceptance of clean energy solutions at the household level.

Additionally, the government has established a dedicated fund through Bangladesh Bank to support women entrepreneurs in the energy sector, although this fund remains underutilized. Leveraging this financing could further promote women’s participation and entrepreneurship in clean energy.

Policy Initiatives and Government Goals

The government of Bangladesh integrates climate action into its national development strategies, with 6-7% of the annual budget allocated to climate adaptation. It aims for universal electricity access by expanding generation and distribution networks to connect an additional 450,000 households per month. Renewable energy projects, especially solar energy, will play a crucial role in meeting these targets. Scaling up investments and addressing grid integration challenges are essential for accelerating the energy transition and making it more inclusive.

The Path Forward

To fully achieve a just energy transition, Bangladesh must address several key areas:

- Scaling Renewable Energy Projects: Expanding solar, wind, and other renewable energy capacities to ensure a more balanced energy mix.

- Grid Modernization: Upgrading infrastructure to accommodate the increased integration of decentralized and renewable energy sources.

- Gender Inclusion: Increasing women’s participation in the energy workforce and leadership positions through targeted training, financing, and policy support.

- Policy Alignment and Financing: Utilizing existing funds and creating new financial mechanisms to support small and medium-sized renewable energy projects, particularly for women entrepreneurs.

Bangladesh’s ongoing efforts in the energy sector highlight the country’s commitment to a sustainable, resilient, and inclusive future. By continuing to integrate gender equity into the energy transition and addressing current challenges, Bangladesh can further solidify its path toward a just and prosperous clean energy future.

As an emerging nation, Bangladesh is currently grappling with various challenges in securing its energy needs, particularly the requirement for dependable and sustainable energy sources. The country primarily depends on natural gas, coal, and oil to fulfill its energy requirements. However, these conventional energy sources are limited and non-renewable, and their utilization contributes significantly to environmental issues, including air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. In contrast, hydrogen fuel presents itself as a clean and renewable energy alternative that could transform Bangladesh’s energy landscape.

Hydrogen fuel is a fuel produced by extracting hydrogen from sources like water or natural gas, which can then be utilized to power vehicles or generate electricity. The adoption of hydrogen fuel as an energy source is increasing because of its clean and renewable characteristics. Hydrogen fuel cells generate electricity by merging hydrogen and oxygen, with water vapor being the only byproduct of this process. One of the primary benefits of hydrogen fuel is its environmental advantages. Hydrogen fuel generates no greenhouse gasses or toxic pollutants, rendering it a clean and sustainable energy option. Another benefit of hydrogen fuel is its widespread availability. Hydrogen is the most plentiful element in the universe and can be sourced from various materials, such as water and natural gas. This indicates that hydrogen fuel is a renewable energy source that can be generated locally, thereby decreasing dependence on imported fossil fuels.

Bangladesh is investigating hydrogen fuel as a viable clean energy alternative. With an increasing need for energy, the nation finds its conventional energy sources, like natural gas and coal, to be limited. Implementing hydrogen fuel could enable Bangladesh to satisfy its energy needs while decreasing dependence on non-renewable resources. The use of renewable energy technologies for producing green hydrogen holds great promise for Bangladesh. Establishing hybrid renewable energy facilities along the coast of the Bay of Bengal, including locations like Kuakata, Sandwip, St. Martin, Cox’s Bazar, and Chattogram, could effectively address the power demand issues in Bangladesh.

One sector where hydrogen fuel may be especially beneficial in Bangladesh is transportation. The nation has a substantial transportation industry, with most vehicles utilizing fossil fuels. Implementing hydrogen fuel in this sector could greatly cut down on greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, resulting in better air quality and enhanced public health. Apart from transportation, hydrogen fuel has the potential to produce electricity in Bangladesh. The nation has been putting resources into renewable energy, including solar and wind, yet these options are variable and can lack reliability. Employing hydrogen fuel cells for electricity generation could offer a steady and dependable supply of clean energy.

While hydrogen fuel offers many potential advantages, there are also significant challenges to overcome. A primary challenge is the high expense associated with producing and storing hydrogen fuel. At present, the production costs of hydrogen fuel surpass those of conventional fossil fuels, and the necessary infrastructure for its storage and distribution is also costly. Another issue is the safety related to hydrogen fuel. As a highly combustible gas, hydrogen requires stringent safety protocols to prevent accidents. Furthermore, there are worries about the possibility of hydrogen leaks, which could pose risks to both the environment and public health.

Bangladesh has established its first hydrogen energy laboratory along with a small hydrogen production facility in Chittagong, a coastal city in the southeastern region of the country. This facility was officially opened by the Bangladesh Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (BCSIR) on January 20th, 2021. The plant will initially utilize waste and biomass as its input materials. It is anticipated that this facility will significantly contribute to the hydrogen sector in Bangladesh and achieve an important research and development milestone that will facilitate the establishment of large-scale hydrogen production plants for commercial and industrial use. Additionally, there are plans to incorporate water electrolysis technology for hydrogen production in the near future. This project aims for the research and quality control related to hydrogen production, storage, supply, and infrastructure development. However, study and research shows that the Solar PV based green hydrogen production is considered promising and cost effective. The potential of this approach is yet to be explored in Bangladesh. This is a solar boom country. Using solar power to produce green hydrogen might become a prospective business, here. A study of Hydrogen Energy Storage Based Green Power Plant (Solar-Wind hybrid model) in the seashore of Bangladesh shows that per unit cost of the system is 0.09$/kWh. It identifies that the green hydrogen production scheme can be used to store renewable energy in an environmentally safer way. However, the study does not analyze the production cost of hydrogen separately. Beside this the power production model includes a power generator which uses hydrogen as fuel.

Also, Rupantarita Prakritik Gas Company Limited (RPGCL) has established a team to examine data from current research and initiatives in developed countries regarding sustainable and dependable hydrogen production methods for fuel. This team will draft a project proposal once they gather satisfactory information. It is anticipated that experimental use of hydrogen fuel in the country will be feasible by 2035.

Hydrogen fuel holds the promise of transforming the energy landscape in Bangladesh. With the increasing energy needs of the country, hydrogen fuel could satisfy this demand while decreasing dependence on fossil fuels. Implementing hydrogen fuel in the transportation sector could greatly lower greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, thereby enhancing public health. Nonetheless, there are challenges that must be tackled, such as the significant expenses related to hydrogen fuel production and storage, as well as the safety issues that arise from its use.

S.M. B.Baque, M. K.Kazi, O. M.Islam, S.Barua, S. M. Mahmud andM. S.Hossain, “Hydrogen Energy Storage Based Green Power Plant in Seashore of Bangladesh: Design and Optimal Cost Analysis”, IEEE Intl. Conf. on Innovations in Green Energy and Healthcare Technologies, 2017.

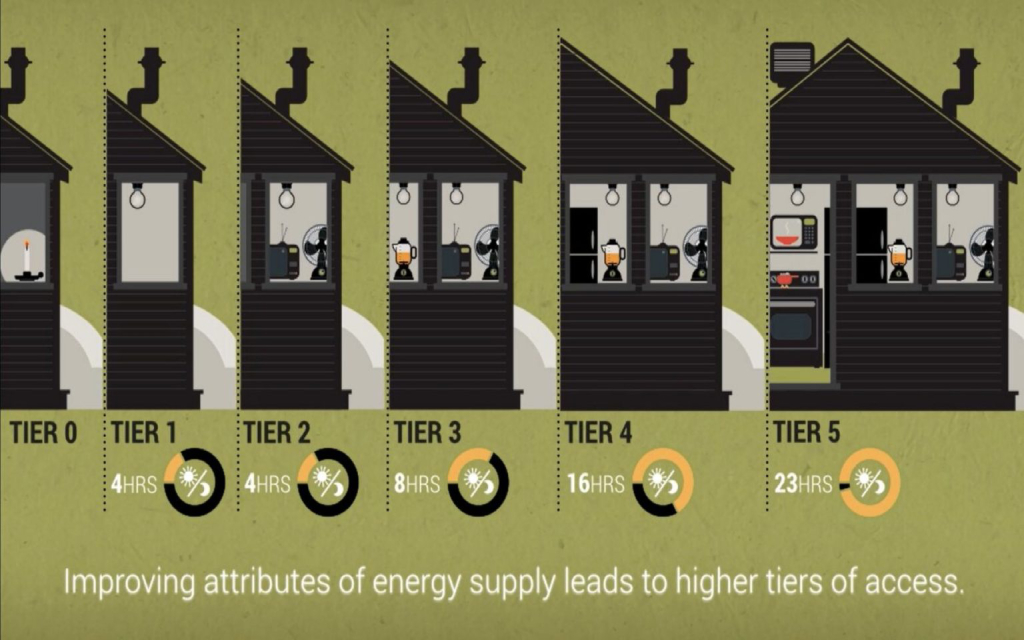

Energy sources like electricity and LPG along with other renewables are recognized as modern forms of energy which unfortunately is used sparsely in developing countries (ESMAP, 2003, p.7; Day et al., 2016, p.257). Improving the availability of reliable and affordable energy carriers for the realization of modern energy services has been the essence of achieving global energy access. Access to energy supply in accordance with Bhatia & Angelou (2015), is “ability of end user to utilize energy supply that can be used for desired energy service” (p.viii). Access to modern energy sources possess undeniable nexus with socio-economic development of developing nation. Since, access to modern forms of energy is closely associated with overall development of nations, there needs to be a clear understanding of existing energy access situation, level of energy access and energy services. Baseline data with reflection of the modern energy access situation can therefore be helpful in strengthening the nexus between energy and socio-economic development. Regardless of electricity supplying technology, in the past electricity access has been measured through binary variables “Yes” or “No” or “have access” or “don’t have access” (Jain et al., 2015). Binary approach is ineffective in capturing true scale of electricity deprivation at certain village or household level due to its inability to address multi-dimensional aspect of electricity access. The binary definition of measuring electricity access is not able to capture difference in quality and quantity of electricity supplying technologies (Practical Action, 2013, p.28). With a binary approach of measuring electricity access, a household with electricity supply from 20 Wp SHS or solar lantern and another household with electricity supply from national grid, both will be viewed as households having similar type and level of electricity access which is not true. There exists a big difference in terms of electricity services that a household can derive from electricity produced by SHS and national grid. The binary approach fails to capture other dimensions of electricity supply which includes ability of supply system to support all kinds of electrical appliances (low power to very high power), erratic nature of supply system and duration of supply. Nepal as of now is following binary approach to measure electricity access. Household are categorized as having access to electricity if there is presence of electricity either from national grid or off-grid electricity supply system. But in recent time, Government of Nepal has adopted MTF to measure the electricity access to keep track of universal target set by SE4ALL and SDG (Goal: 7) (NPC, 2018, p.2). The stark disparity between rural and urban areas can be better scrutinized following a multi-dimensional approach to measure electricity rather than binary approach. The electricity access disparity share between rural and urban areas might be different to that of disparity figure given by binary approach (World Bank, 2017, p.24). A village in India was said to be electrified if 10 percent households had access to electricity. As a result, 96.7 percent of Indian villages were found to be electrified which was not the real case (Jain et al., 2015, p.31). Such binary approach yields spurious statistics regarding share of households having electricity services. Due to presence of anomalies in binary approaches, multi-dimensional access measuring metric; Multi-Tier Framework (MTF) is gaining popularity in measuring electricity access.

Multi-Tier Framework (MTF): Planning for Electricity Access

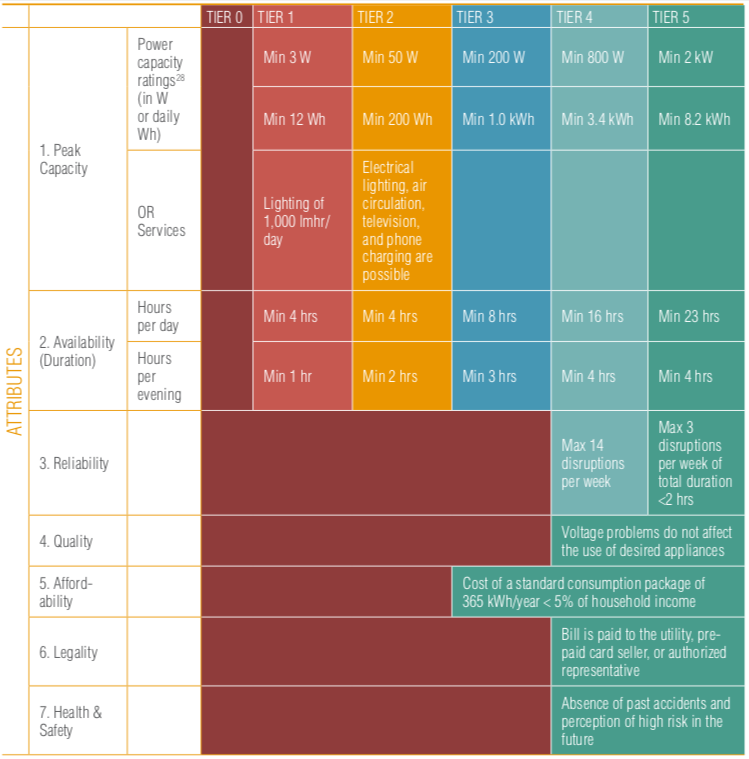

Under SE4ALL, the Global Tracking Framework (GTF) 2013 introduced Multi-Tier Framework (MTF) to measure energy access (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015, p.1). The MTF has provided number of attributes and dimensions, based on which electricity access is measured. There are seven attributes; capacity, duration, reliability, quality, affordability, legality, and health & safety; each of which defines various dimension of electricity supply system. Electricity access is measured with respect to seven different attributes across which electricity supply situation for a household is analyzed. Each attribute is analyzed, and results are expressed in terms of tier; Tier 0 being the worst level of access while Tier 5 is best access level at household level. According to the decision rule of MTF, final tier of electricity supply is determined by the lowest tier obtained across all seven attributes of electricity supply (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015, p.5). The MTF attributes for electricity access measurement are shown in Figure 2-1. Figure 2-1: MTF Matrix for Measuring Electricity Access for Households Source: (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015, p.6).

MTF approach to measure electricity access enables energy planners and policy/decision makers to identify appropriate level of electricity in the form of tier and amount of investment required to reach the target tier (World Bank, 2017, p.xv). Defining energy access with respect to attributes will be helpful in identifying interventions such as technology implementation, policy development or capacity building endeavor required to improve electricity access level. Scrutinizing every electricity access attribute is useful in identifying major challenges that is impeding improvement in energy access. For a country or region, MTF can elucidate the reason for them being unable to upgrade electricity access tier (World Bank, 2017, p.24). According to Bhatia & Angelou (2014), “multi-tier measurement of energy access allows government to set their own target by choosing any tier above tier 0” (p.7). Based on available resources, timeframe and geographical challenges, local government may decide which tier they would like to aim for based on baseline information of household tier.

Source: (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015)

The MTF has already been experimented as tool to devise energy access plan in Bangladesh, Kenya, and Togo (Practical Action, 2014, p.2). Classification of households into tiers gives wider perspective of type of energy access prevalent in certain area/village/location of interest. This helps to visualize challenges and factors that are impeding to improve the energy access situation of households in areas affected by poor supply of energy. As emphasized by Jain et al., (2015), the advantage of using MTF is the identification of variation involved in energy supply and access situation in certain region. Moreover, MTF has been used to enunciate country action agenda to meet SE4ALL objectives (Pelz et al., 2018a).

On a global scale, the level of electricity access is desired at Tier 3, but MTF provides flexibility to member states to set up plans to reach the global target as much as possible (NPC, 2018, p.3). Kenya in its SE4ALL action agenda has planned to improve its energy access situation according to the MTF-tier concept. By 2030, Kenya plans to secure 35 percent household to be at tier 3, 15 % at tier 4 and 10 percent at tier 5 while 40 percent below tier 3 (Practical Action, 2014, p.64). For the member states of United Nation agreeing to comply SE4ALL and SDG (Goal: 7) initiatives, tools such as MTF should not only be able to measure the progress but also assist member state governments and concerned organization to devise concrete plan and policies by providing noticeable evidence (Pelz et al., 2018b).

Multi-Tier Framework Critique

The MTF provides a tool that can be used to measure energy access across the globe. Although MTF can address shortcomings of binary metrics to measure energy access, there exists argument regarding generalization of MTF approach to measure energy access (Pelz et al., 2018; Tait, 2017; Groh et al., 2016). Generalization of MTF to measure energy access in different countries across the world reduces its usefulness as a tool for national energy planning. MTF requires certain level of national adaptation to obtain tangible results regarding energy access situation with respect to diversity existing between different regions and countries (Groh et.al., 2016; Tait, 2017). Nevertheless, the classification of tiers to evaluate access to energy services is necessary and valuable to understand the baseline status of energy access for a particular region and develop plan for improvement in future. Generalization of the global energy access measuring metrics falls short in addressing gaps existing between the developed, developing and least developed country. There exist country specific factors such as geography, culture and socio-economic status of the nation and its citizen which may not be addressed by generic tools such as MTF (Tait, 2017). Furthermore, the energy service need may vary from one household to another due to their preference of appliances or culture (Pelz et. al., 2018, p.3). The way of living, cultural behavior, the quality of energy services that the end user is receiving, desire to climb up the energy ladder and use of modern appliances also impacts the result of electricity access measurement. The measurement of energy access based on MTF attributes might need adjustment as per country specific context due to existence of diverse energy needs and factor affecting those needs. The MTF approach has been adapted in the past to measure electricity access level. Tait (2017) analyzed energy access status in South Africa using just four attributes: fuel consumption, affordability, safety, and reliability without categorizing household into MTF tiers. According to the assessment made by Tait (2017), the indicators used for the measurement of electricity access were analyzed based on the score such that 1 being better access and 0 being the worst. Jain et al., (2015) made use of MTF and adapted it to Indian context by using four tiers instead of six tiers to visualize level of energy access. Furthermore, the availability attribute has also been analyzed over a period of a day which is slightly different from availability attribute mentioned in MTF that considers electricity supply in evening hours. There exists argument over maintaining simplicity and uniformity in use of availability attribute across the world (Jain et al., 2015; Pelz et al., 2018). The development status gap between global north (developing and least develop country) and global south (developed country) and global south represented by developing and least develop country pose challenges in generalizing MTF around the world. Global south is more inclined towards commissioning modern energy infrastructure to fulfil energy needs of their population with priority on energy efficiency while global north is more focused on improving energy efficiency and thereby reducing their share of carbon footprints (Day et al., 2016). The challenge of generalizing further exacerbates as the MTF in its current state is not able to address impact of energy efficiency endeavors on requirement of capacity of energy supply system (Pelz et al., 2018). Establishing a common threshold value for energy access measuring attributes has been subject of argument. There have been several examples where the threshold value to determine level of electricity access has been altered by researchers. In Indian context, the legality attribute has been emphasized while in South African context legality attribute has not been considered with an argument of illegal connection for electricity being better source for lighting compared to primitive alternative like candle. Similarly, health and safety attribute were not captured citing in Indian context in absence of comprehensive data that could address health and safety attribute (Jain et al., 2015; Tait, 2017). Depending upon the context and situation one may decide what kind of information is required to compute MTF attributes with less complexity.

The MTF tier approach to measure electricity access clearly defines the kind of electricity service that can be derived from different tier of electricity access. The electricity access tier in these households needs gradation. But from planning perspective knowing a target tier for rural households is inevitable. Understanding appropriate target tier for electricity access is essential as it provides strong basis to develop electricity access vision and subsequently vision driven interventions in the form of plan and policies.

References:

- Bhatia, M., & Angelou, N. (2014). Capturing the Multi-Dimensionality of Energy Access. Livewire, 1–8.

- Bhatia, M., & Angelou, N. (2015). BEYOND CONNECTIONS Energy Access Redefined

- Day, R., Walker, G., & Simcock, N. (2016). Conceptualizing energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework. Energy Policy, 93, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.019

- ESMAP. (2003). Household Energy Use in Developing Countries – A Multicounty Study, (October)

- Groh, S., Pachauri, S., & Narasimha, R. (2016). What are we measuring? An empirical analysis of household electricity access metrics in rural Bangladesh. Energy for Sustainable Development, 30, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2015.10.007

- Jain, A., Ray, S., Ganesan, K., Aklin, M., Cheng, C., & Urpelainen, J. (2015). Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity. ACEESS – Survey of States, 1–98. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0NV9LF 93 Javadi, F. S., Rismanchi, B., Sarraf, M., Afshar, O., Saidur, R., Ping, H. W., & Rahim, N. A. (2013). Global policy of rural electrification. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 19, 402–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.11.053

- National Planning Commission. (NPC). (2018). Universalizing Clean Energy in Nepal. Retrieved from https://www.npc.gov.np/images/category/SUDIGGAA_final_version.pdf

- Pelz, S. (2018). Inclusive Energy Access Planning. Retrieved from https://reiner-lemoineinstitut.de/en/inclusive-energy-access-planning/

- Practical Action. (2013). Poor People’s Energy Outlook 2013. Retrieved from http://cdn1.practicalaction.org/5/1/5130c9c5-7a0c-44c9-877f-21b41661b3dc.pdf

- Practical Action. (2014). Poor people’ s energy outlook 2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Tait, L. (2017). Towards a multidimensional framework for measuring household energy access: Application to South Africa. Energy for Sustainable Development, 38, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2017.01.007

- The World Bank. (2017). State of Electricity Access Report 2017. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26646/114841-WP-v2- FINALSEARwebopt.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

- 1. Background

Electricity supply in Nepal is largely dominated by hydropower plants. Over 96% population has access to electricity in Nepal. Hydropower is the primary source of electricity, contributing 92.1% of the total supply. The remaining share is derived from solar energy (4.7%), other renewables (1.2%), bagasse (0.2%), and thermal power plants (1.7%). These figures indicate that Nepal is heavily reliant on hydropower plants for electricity generation. Recent flooding events in the country has wreaked havoc in many development sectors and infrastructures withing energy sector. The Ministry of Energy, Water Resources, and Irrigation (MoEWRI) reports that recent flooding has resulted in losses and damages totaling 3 billion Nepalese Rupees in the energy sector, affecting electricity production from 11 hydropower projects with a combined capacity of 625.96 MW. Lesson from the recent flooding is that there is a dire need for diversifying energy mix in the country. Furthermore, in a country where centralized transmission and distribution systems continue to struggle to supply reliable and quality electricity, decentralization, and diversification of national energy mix with energy sources like solar is essential to improve the reliability of the power supply system.

Bifacial Solar PV panel installed at Sanepa Apartment

Photo Courtesy: Gham Power Pvt. Ltd

Nepal has a significant potential for solar energy, as indicated by Solar GIS, offering a path to diversify its electricity sources. Recently, innovative solar technologies have emerged, such as the one piloted by the 2022 Grid Resilience through Intelligent Photovoltaics and Storage (GRIPS) project. Funded by the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office through the Innovate UK Programme – Energy Catalyst, GRIPS was implemented by a consortium including Swanbarton UK, Gham Power Nepal, Practical Action Consulting, Scene Connect UK, and Hit Power UK. The project piloted a 57 kWp smart solar-storage system in a commercial apartment in Lalitpur to enhance energy reliability and demonstrate its benefits for utilities, consumers, and energy providers. Practical Action Consulting contributed to assessing societal impact and promoting GESI integration within the solar PV sector and energy access market.

With the successful conclusion of the GRIPS project, this blog highlights key learnings and findings, emphasizing Practical Action Consulting’s project objectives. As a pilot initiative, the insights gained is expected to inspire energy professionals, development practitioners, and stakeholders to drive the energy transition while incorporating GESI within the renewable energy sector.

- 2. Gender in Solar PV Market Systems of Nepal

Achieving gender equality, empowering women, and ensuring universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy by 2030 are interconnected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with numerous cross-cutting benefits. Growing evidence shows that integrating gender considerations throughout the energy value chain and power sector brings multi-level benefits, significantly enhancing socio-economic conditions in any society. However, gender disparities in energy access and the power sector workforce impact critical sectors like health, education, food security, transportation, agriculture, water, sanitation, and entrepreneurship. Drawing on Practical Action Consulting’s 2023 gender assessment of Nepal’s solar PV market (involving 11 solar companies), stakeholder consultations, and literature reviews on the gender-energy nexus, this blog examines the status of women and marginalized groups in Nepal’s energy sector. It also highlights key entry points for development partners to contribute to advancing women’s empowerment and participation within Nepal’s solar PV market.

Stakeholder Consultation Meetings

- 3. Rationale to Gender Considerations in the Energy Discourse

Limited access to clean, modern energy and reliance on traditional fuels have significant consequences, including drudgery, adverse health effects from exposure to air pollution, deforestation, time poverty, and missed opportunities for economic and personal growth (see Box 1). At the household level, women are disproportionately affected by the lack of modern energy access due to their primary role in household tasks such as cooking, farming, collecting firewood, and gathering water. Gender norms and varying responsibilities mean that women and men often have different energy needs and unequal access to energy services and technologies. To ensure equitable access and benefits from energy services for both women and men, it is essential to make the energy sector gender-responsive and gender-transformative through supportive policies, inclusive projects, and gender-sensitive services. Additionally, encouraging women’s active participation in the energy sector as decision-makers, entrepreneurs, business owners, and employees is crucial. Research shows that gender diversity, especially in leadership roles, can enhance the sector’s performance and drive greater social and economic gains.

Box 1. Social Implication of access to clean and modern energy solutions:

- Social Capital/Empowerment-Access to energy can offer access to modern communication and networking opportunities.

- Livelihood – Enhanced livelihood and improved income through productive end uses of energy

- Reduced use of fossil fuels and trade deficit – Reduced dependence on imported fossil fuel

- Environment – Reduced air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (from traditional and fossil fuels), hence improvement in human well-being and environmental protection.

- Health – Access to power for operating modern health equipment and hence increasing possibilities of better health services.

- Gender equality – Reduced drudgery and time saving, hence increased opportunities for education, personal growth and income generating activities especially for women.

- Security – Light provides safer working environment and security for mobility into the late hours.

- 4. Current Status of Women in the Solar PV and the Energy Sector at Large

- a.Energy sector employments and energy value chain

Women remain significantly underrepresented in Nepal’s energy sector. At the Nepal Electricity Authority (nodal agency responsible for electricity supply), for instance, only 12.6% of the total 8,884 employees and 6.2% of the 5,664 technical staff are women. Practical Action Consulting’s 2023 Gender Audit Study, conducted at 11 solar PV companies, revealed that women make up only 19% of the workforce in the solar PV sector, and predominantly hold non-technical roles. Only one company employed women in technical roles, where two out of six technical staff were women, while women held just 22% of senior positions across the companies studied.

In terms of economic participation and educational attainment, Nepal ranks low globally, placing it at 136th rank in the 2023 Gender Gap Index with a 47.6% gender gap in economic opportunity, and 127th for gender disparity in education. Despite efforts by solar PV companies to encourage women to apply for technical roles, they reported that they receive only few female applicants. This may be partly attributable to low enrollment rates of women in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. According to the 2021 National Population Census, only 15% of engineering graduates and 34% of science and technology graduates were women, with similarly low participation in technical training programs.

- b. Energy sector employments and energy value chain

A comprehensive review of Nepalese energy and solar PV policies reveals they are largely gender-aware, acknowledging gender in policy frameworks and programs. However, these policies often lack in-depth strategies to integrate gender considerations effectively into energy initiatives,7. While Nepal has set SDG 5 targets, aiming for 30.3% women’s representation in decision-making roles in the private sector and 28% in professional and technical roles, there is no specific energy policy to ensure equal opportunities for women in the private energy sector. Current energy policies focus heavily on production and supply, with minimal emphasis on social inclusion, women’s empowerment, gender equity, equality, and intersectionality. Some policies, like the Renewable Energy Subsidy Policy 2022 and the National Energy Strategy of Nepal 2013, include provisions for marginalized groups but lack robust gender-responsive measures to achieve GESI objectives. Significant efforts are still needed across various levels to enhance the participation of women and marginalized groups in managing, planning, designing, and implementing energy policies and programs.

- c. Common barriers to women’s participation in the energy sectors

- Gender biases and stereotypes often hinder women from pursuing challenging roles outside the home. Technical jobs are typically seen as men’s work, while women are associated with roles in the care economy and support work. This is reflected in the power sector, where women employees are largely concentrated in administrative rather than technical positions.

- Household chores and unpaid work are often seen as women’s responsibility, regardless of employment status. This additional burden can discourage women from pursuing demanding roles or leadership positions outside the home.

Limited access to resources, particularly finances, poses a major challenge for female entrepreneurs in energy businesses and for women consumers seeking energy technologies and services. - A lack of gender considerations in energy project and product designs has been cited by many studies as one of the reasons why women are disproportionately affected by a lack of access to clean and reliable energy sources.

- Wage discrimination and unequal distribution of resources/services (appropriate size safety gears, toilet, water and sanitation, and childcare services, etc.) between men and women are also seen as factors discouraging women to seek power sector jobs7.

Absence of gender and social safeguarding policies and transparent hiring processes can also affect the employment and retention of women staff in any company. - A lack of capacity building, leadership development, technical training opportunities and mentoring support also affect women employees’ self-confidence, sense of security and belonging in the technical fields within the energy sector.

- Limited access to information and professional networks impedes professional growth of women and marginalized groups.

The absence of gender-disaggregated data and the limited ability of energy professionals to incorporate gender into policies and programs hinder the creation of gender-responsive energy plans and market systems. Socio-cultural contexts create informal barriers to the empowerment and participation of women and marginalized groups, while formal barriers, such as gender-blind policies and practices, reinforce the status quo. This brief will not cover all barriers but will highlight gender considerations and best practices, focusing on gender equality and social inclusion in the energy workforce and access to energy solutions.

- 5. Way Forward – Policy Implications

- The development and implementation of GESI policies and strategies (e.g., Nepal Electricity Authority GESI Strategy and Operational Guidelines 2020; Alternative Energy Promotion Centre GESI Policy 2018) are essential first steps toward removing barriers to the participation of women and marginalized communities in the energy sector. However, changing organizational culture requires internalizing these policies by i) building the capacity of both managerial and implementation staff to integrate GESI considerations into energy-related activities, and ii) incorporating GESI policies into the key performance indicators of all departments and projects. Effective policies must be supported by institutional capacity and robust monitoring systems.

- It is important to acknowledge that women and marginalized groups are not just energy users, but they can also become employees, social change agents, entrepreneurs and participants in the energy value chain, and decision makers in energy project planning and implementation. Nevertheless, a very low participation of women in the technical education and employment is a frequently cited challenge in achieving gender equality across the energy sector and the energy value chain. Several measures can be adopted to increase women’s participation in the STEM education and employment – targeted scholarships in STEM programs; internship opportunities for female STEM graduates; targeted recruitment of women staff; addressing gender pay gaps; adopting transparent hiring and promotion processes; setting organizational gender equality goals; compulsory courses on Sexual Harassment, Exploitation and Abuse (SHEA) and Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) at workplace for new recruits and Human Resource team of the organization; mentoring and leadership programs for women staff alongside their male counterparts; reorientation programs for mothers returning from maternity leave; and flexible work hours for parents of young children.

- To create a gender-inclusive business model for energy products and services, it is vital to consider the needs and aspirations of women and marginalized communities in project design and delivery. Each component of a business model—goals (economic and social), products/services, target demographics, and delivery methods—offers opportunities to foster a gender-responsive energy value chain system.

- Business goal: While profit-making is crucial, to create social impacts and set gender equality goals are as crucial for a solar company or any energy company to improve its gender profile and to be able to tap into opportunities created by development programs (such as Green Climate Fund, Energy Catalyst Program, etc.)

- Products and services: Energy interventions, technologies, energy services and other support services (financing, repair, and maintenance, etc.) are more likely to address gender equality and energy poverty issues when women and marginalized groups’ needs and purchasing power are considered in their designs.

- Demand or target group: Social impacts of energy solutions can be maximized when they are delivered to the population for whom the energy solutions have the greatest marginal utility – at household and community level, it is often women and low-income families.

- Delivery model: Engaging women in the energy value chain, enabling women and low-income households to access energy services (which may not necessarily mean the ownership of the energy system), using women networks/organizations and gender-responsive mechanisms to deliver energy products and services, and relevant information to last mile markets are some of the tested and proven strategies to make delivery model of energy solutions gender-inclusive.

- Evidence shows that if training contents and tools are adapted to match the needs of women, they (regardless of their educational qualifications) can effectively learn skills and take on technical roles and responsibilities such as installing and operating renewable energy technologies (see box 2. for an example). While experts suggest that women’s participation in technical trainings is usually low, practitioners suggest that targeted trainings and quota systems can increase their participation in such trainings enabling them to become a change agents and value chain actors.

Box 2. Case story – ‘Solar Mamas’ lighting a remote village of Nepal

In 2018, three women from a remote village in Humla region of Nepal, with no formal education, were trained by Barefoot College International (BCI), India with support from various non-governmental organizations. The six-month training enabled them to assemble, install, operate, and repair Solar PV Home Systems such as solar lanterns, lamps, solar water heaters and parabolic cookers all by themselves. The training program at BCI is tailored to accommodate rural women from different age-groups and countries regardless of their educational backgrounds and uses tools and techniques that address any challenges with language barriers. In addition to learning technical skills, they also learned about entrepreneurial skills, women’s rights, health, and safety, how to use mobile phones, English language, and environmental stewardships. The trained women, or ‘Solar Mamas’ after returning home, have made electricity services accessible in their village. Their village, otherwise, has no access to the central grid or any other source of modern energy. As of 2021, the ‘Solar Mamas’ from Humla had electrified 220 households and had benefitted over 2100 people.

- Availability of gender-disaggregated data on the impacts of energy projects and the energy workforce, and the analysis of these data and GESI performance indicators in impact reports are important to track progress of the sector towards gender equality and social impacts, and to inform actions and strategies towards gender-equality goals and a gender-responsive energy sector.

India’s trucking industry, integral to the nation’s economic framework, underpins logistics and goods transportation across the country. This sector accounts for a significant share of domestic freight movement, supporting industries from agriculture to e-commerce. However, it also shoulders a heavy environmental burden. Diesel-powered trucks contribute significantly to greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, aggravating public health crises and environmental degradation. Moreover, the sector’s reliance on fossil fuels makes it economically vulnerable. India’s dependency on oil imports not only exposes trucking operations to volatile fuel prices but also undermines energy security. Transitioning to Zero Emission Trucks (ZETs)—including battery-electric and hydrogen-powered trucks—offers a plethora of advantages: reducing emissions, strengthening resilience against fluctuating fuel costs, enhancing national energy security, and more. The shift to ZETs, while essential, is a complex process, especially for the small and medium fleet (SMF) operators who dominate the industry.

Key Challenges of Transition

The move to ZETs requires a phased approach, with timelines varying across use cases such as long-haul freight, drayage, regional return-to-base, and non-return-to-base operations. Fleet operators face numerous challenges in this transition: