Carbon neutrality or net-zero carbon dioxide emissions entails balancing emissions of carbon dioxide with its removal or by eliminating emissions from society. While 2020 was a bleak year, owing to the Covid crisis, it ended with some hope for the planet when a group of developed countries – USA, Canada, Japan declared their resolve to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. China declared that it would be able to achieve the same by 2060. There is a growing pressure on India too to declare this as such but Indian Government has stated clearly that it cannot possibly do it alone, and without jettisoning the project of pulling millions living in poverty in the country.

The declarations of the developed country is being seen as a timely declaration coming along with Special Report on 1.5 degree Celsius. There are several cities, municipalities, and businesses world over which are declaring net zero targets in 2050.These numbers are climbing quickly, particularly because the U.N. Secretary General asked countries to come forward with net-zero targets. The U.N. High Level Climate Champions’ Race to Zero campaign also calls on regions, cities, businesses, investors and civil society to submit plans to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 in advance of the United Nations climate negotiations (COP 26) in Glasgow in November 2021. The Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5˚C, from “the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), finds that if the world reaches net-zero emissions by 2040, the chance of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C is considerably higher. All in all, the world must try to reach net zero targets as soon as may be. The chances of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees C, however, depend significantly on how soon the highest emitters reach net-zero emissions

Differential Capacity to achieve the net zero target

This does not, however, suggest that all countries need to or can reach net-zero emissions at the same time. WRI (2019) argues that “Equity-related considerations — including responsibility for past emissions, equality in per-capita emissions and capacity to act — suggest earlier dates for wealthier, higher-emitting countries. Policy, technology and behaviour need to shift across the board”. In pathways to 1.5 degrees C, renewables are projected to supply 70-85% of electricity by 2050, which is one of the most important mechanisms through which the goal can be achieved.

India is in a dilemma. It cannot possibly commit to net zero by 2050 without abdicating its responsibility towards its citizens of providing affordable, clean energy, employment, proper infrastructure etc. India has done more than most countries with its level of development and its poverty profile and is trying very hard to reduce its GHG emissions as quickly as possible. This is reflective in India investing heavily in its renewable energy programme and has reiterated its 450 GW target of installled RE capacity by 2030. But is indecisive about announcing its net zero target by 2050. This is because net zero target would require a multi sector, multi-level action, something India sees unlikely to be able to do by 2050. Changes in patterns of energy production and consumption, industrial production and consumption, transport – would all require fundamental changes in which , and while India taking relevant steps, it’s not happening fast enough. India and other nations, through their INDCs has outlined its post-2020 climate actions to contribute toward the 2°C global warming limit. For most countries steps to reach net zero target through decarbonization cover greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction targets in energy, industry, agriculture, waste, land use and forestry, and transport—the sectoral focus varying from country to country. These have been laid down in their respective INDCS.

South Asia and Net Zero

Mitigation targets in the INDCs of various countries are reflective of their efforts and alignment with the 1.5 to 2 degree Celsius target. Where is South Asia at the moment in terms of alignment of its mitigation efforts (expressed in INDCs) to the 1.5 – 2 degree temperature limit? Except for Bhutan and Nepal, South Asian countries provided intended mitigation contribution in terms of percentage reduction in GHG emissions or emission intensity. Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Sri Lanka aim at GHG emission/ carbon intensity reduction ranging from 5% to 24% by 2030, from BAU, with components conditional on international assistance. India commits to reduce emission intensity by 33% to 35% by 2030 compared with 2005. While not providing a specific GHG emission reduction commitment, Bhutan stated intention to remain carbon neutral where GHG emissions will not exceed carbon sequestration by the forests. On the other hand, Nepal’s stated commitments were in terms of reduction in fossil fuel dependency, appropriate mix of renewable energy in energy mix, and maintained forest cover.

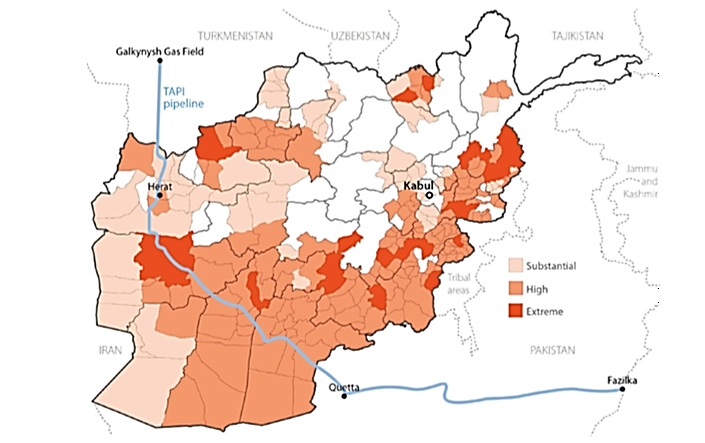

We will look at these for all South Asian countries in some detail through perusal of their INDCs to first enumerate their mitigation targets and then assess their alignment with the 1.5to 2 degree Celsius target. These INDCS are either based on conditional or unconditional international support. Afghanistan in its INDC has committed to 13.6% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 compared with Business-as-Usual (BAU), conditional on external support. These would require financial assistance from the developed countries for its achievement. Bhutan on the other hand seeks to remain carbon neutral where GHG emissions will not exceed carbon sequestration by forests (approximately 6 million tons of CO2).

India has both conditional and unconditional targets, which include – Reduce emission intensity of its gross domestic product (GDP) by 33%–35% by 2030 compared with 2005 (no bind on any sector-specific mitigation obligation/action) • Achieve 40% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non – fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030 (with transfer of technology and low-cost international finance) • Create an additional carbon sink of 2.5–3 billion tons of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030. Nepal’s conditional INDCs include – • Achieve 80% electrification through renewable energy sources having appropriate energy mix by 2050. • Reduce dependency on fossil fuels by 50% by 2050 • Maintain 40% of total area of country forest cover • Sustainable Forest management to increase forest productivity and products.

Srilanka’s conditional and unconditioanal targets include – Reduce GHG emissions by 20% (approximately 36,010.2 gigagram [Gg]) in energy sector by 2030 against the BAU scenario – 4% unconditionally (approximately 7,202.04 Gg) and 16% conditionally (approximately28,808.16 Gg). • Reduce GHG emissions by 10% from transport, waste, industries, and forest – 3% unconditionally and 7% conditionally against BAU scenarios

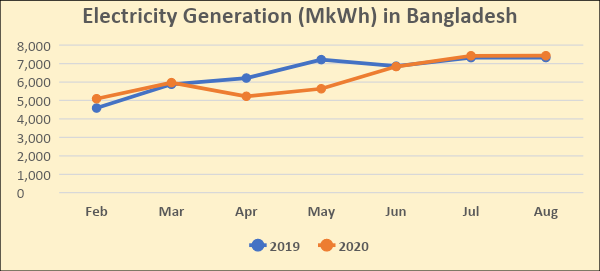

Pakistan’s conditional target is reduce emissions after reaching peak levels (subject to affordability, provision of international climate finance, transfer of technology and capacity building). The conditional and unconditional target of Bangladesh include : Reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 5% (12 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent [MtCO2e]) from BAU levels by 2030 in the power, transport, and industry sectors, based on existing resources • Reduce GHG emissions by 15% (36 MtCO2e) from BAU levels (by 2030 in the power, transport, and industry sectors (subject to appropriate international support on finance, investment, technology development and transfer, and capacity building).

Net Zero for South Asia is a long route

These are the mitigation targets submitted as a part of the INDCs by the South Asian countries to the UNFCCC as a vision they seek and would achieve given financial and technological support they get. These are plans that the countries seek to pursue to contribute to the prevention of climate change. But most of these are not 1.5 – 2 degree Celsius aligned. Its only Nepal, Bhutan and India whose INDCs if pursued rigorously is 2-degree Celsius compatible. The rest are either not or have not submitted sufficient information to be able to infer combability.

| The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) has assessed the fair sharing of the proposed contributions of selected countries on efforts to move global emissions downward through 2030. It provided ratings on intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs), pledges, and current policies, specifically on whether they are consistent with a country’s fair share effort to holding warming to below 2°C.The assessment included six developing member countries of ADB: Bhutan, India, the People’s Republic of China, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, and Nepal. |

| Bhutan’s pledge was rated “sufficient” for 2025, and it is the only country ever rated “Role Model.” This rating is based on emissions excluding land use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) and takes into consideration that, as a developing country with currently very low emissions per capita, Bhutan’s emissions are expected to grow over this time period. Gradual reductions will be needed afterward. |

| India’s pledges were rated “medium.” The pledges are in line with effort sharing approaches that focus on equal cumulative per capita emissions. A “medium” rating indicates that commitments are not consistent with limiting warming below 2°C and greater effort or deeper reductions from other countries are required. Approaches that focus on historical responsibility and capability would require more stringent emission reductions. The “medium” rating indicates that India’s climate commitments are at the least ambitious end of what would be a fair contribution. This means it is not consistent with limiting warming to below 2°C unless other countries make much deeper reductions and comparably greater effort. |

| Nepal has not made any emissions reduction pledge, hence no rating was provided. Its own emissions make up less than 0.1% of global emissions. With its current policies, Nepal’s greenhouse gas emissions are expected to increase by 62% by 2030 compared with 2010 levels. Nepal’s projected emission levels in 2020, 2025, and 2030 are in the “sufficient” range. CAT analysis determined an upper end of the “medium” range for Nepal using effort-sharing approaches based on quality principles. To be in line with approaches that focus on responsibility and capability, Nepal would need to reduce its emissions from its current policy projected levels. Apart from the three countries most have not been assessed.Source: Climate Action Tracke |

Potential for Decarbonisation through Renewable Power Generation in South Asia

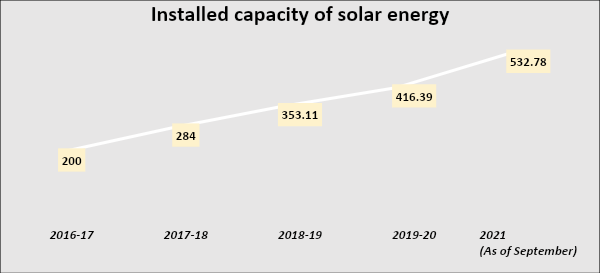

A lack in the INDCs of the South Asian Countries is largely due to the fact that lack of finance and technology has prevented RE potential from being sufficiently exploited. We will now assess the progress and potential of the countries towards their mitigation targets, especially their RE targets. India has set an objective of 450 GW by 2030. India has tremendous potential for solar energy and is also expanding wind energy. By July 2020, India had reached a total RE installed capacity of 86 GW.

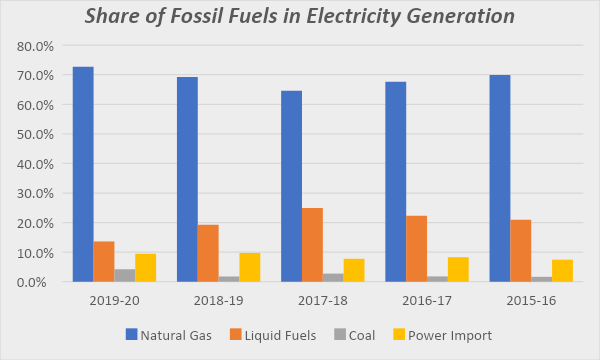

In 2019, Bangladesh had 2.1 percent and 1.2 percent of solar and hydro in the total installed capacity respectively. In Pakistan in 2019, of total installed capacity, 29.4 percent and 4.97 percent were constituted by hydro and solar respectively. According to WB Pakistan has tremendous potential to generate solar and wind power. According to the WB, utilizing just 0.071 percent of the country’s area for solar photovoltaic (solar PV) power generation would meet Pakistan’s current electricity demand. Wind is also an abundant resource. Pakistan has several well-known wind corridors.

As a developing country, Sri Lanka’s demand for electricity is going to increase in the future. It is imperative therefore, for Sri Lanka to secure its energy future by focusing on the development and adoption of indigenous, renewable sources of energy to meet this growing demand and reduce the economic burden of imports. Acknowledging this need, Sri Lanka saw an increase in the share of renewable energy (RE) in the electricity mix, when in 2014, the country met its target of generating at least 10 percent of its electricity using renewable energy. Subsequently, in 2015, the contribution of fossil fuels to the electricity mix decreased, at the same time as a rise in the contribution of both renewable energy and large hydro. In 2019 Srilanka, of the total installed capacity, 34 percent was constituted by wind and 3.6 percent by solar.

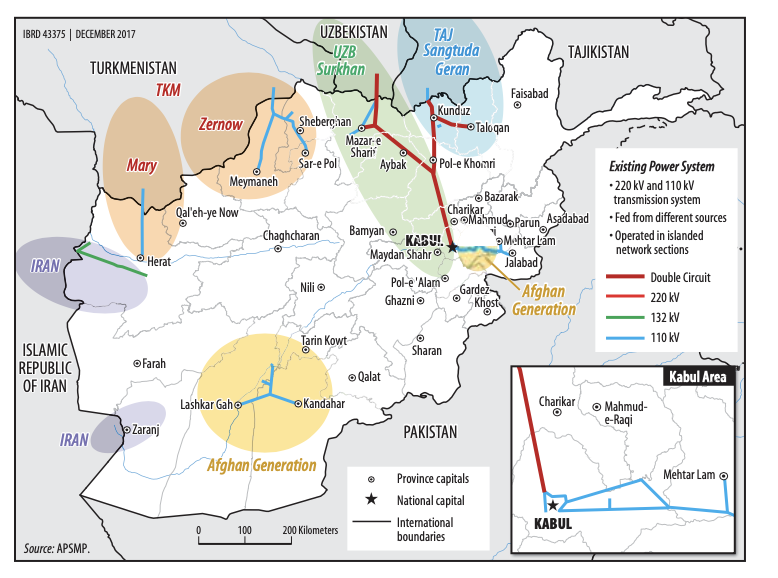

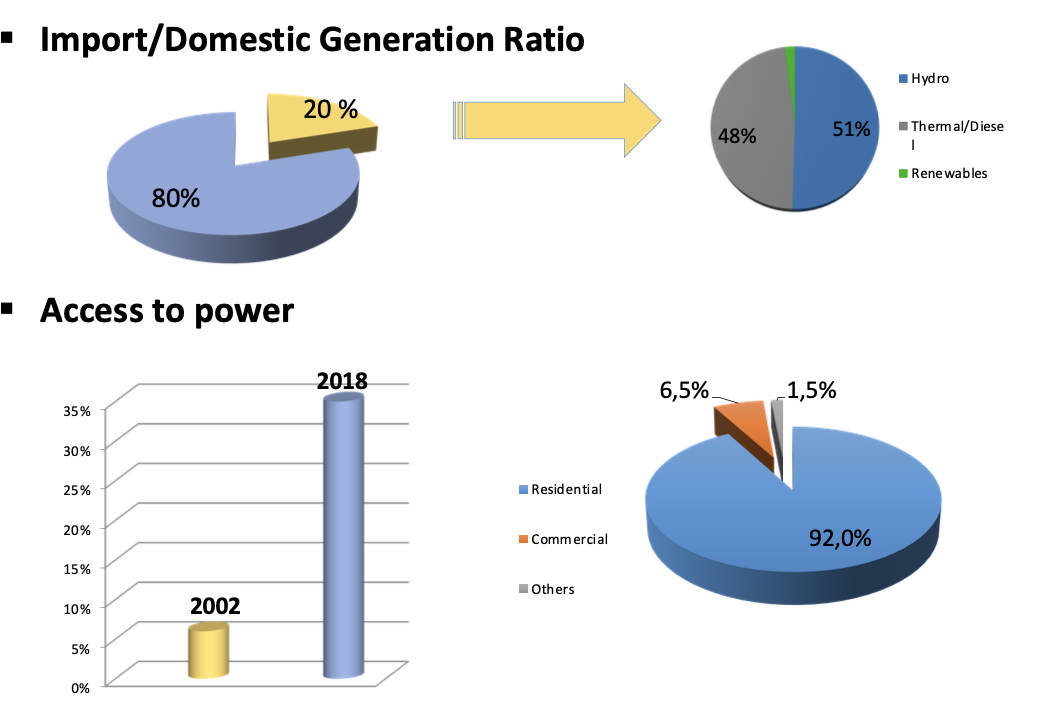

Maldives is Infact totally dependent upon fossil fuels and, in 2019 had only 4.9 percent of solar in the total installed capacity. Maldives is located in the Equator and receives abundant solar energy. Maldives Receives about 400 Million MW of Solar Energy Per Annum and tremendous potential for wind energy. Other forms of RE need to be exploited as well but lack of financing, technical capacity and infrastructure has so far prevented it from happening. Nepal and Bhutan almost completely rely on hydropower, and other forms of RE need to be explored. In 2019, Nepal of the total installed capacity, 70.7 and 24.9 percent were constituted by large and small hydro respectively. And Bhutan had 99.93 percent of hydro of the total capacity. Afghanistan as of now depends upon imported diesel but has tremendous solar potential, which can be exploited in future. In 2019, Afghanistan had established of the total installed capacity, 53.1 percent of hydro. More needs to be done to decarbonize power sector in South Asia by involving RE in the fuel mix. This however requires climate finance which is not available to these largely poor developing countries. (The information on installed capacity for various countries has been drawn from Energy Transition Platform hosted by the Vasudha Foundation).

Can SAARC provide the answer?

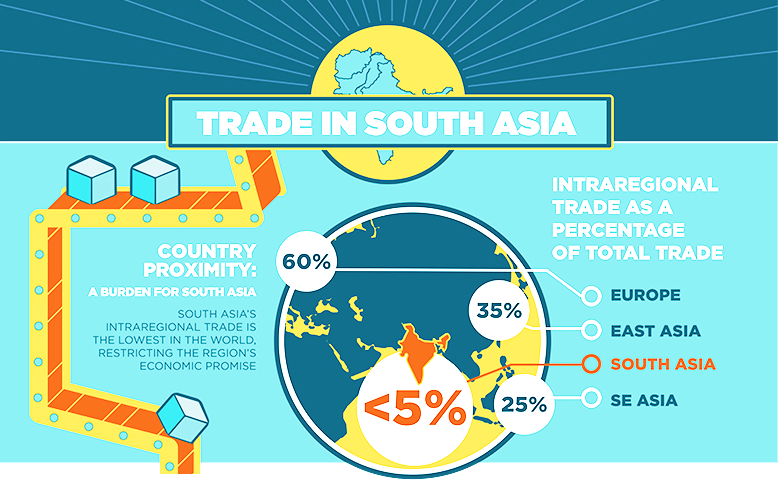

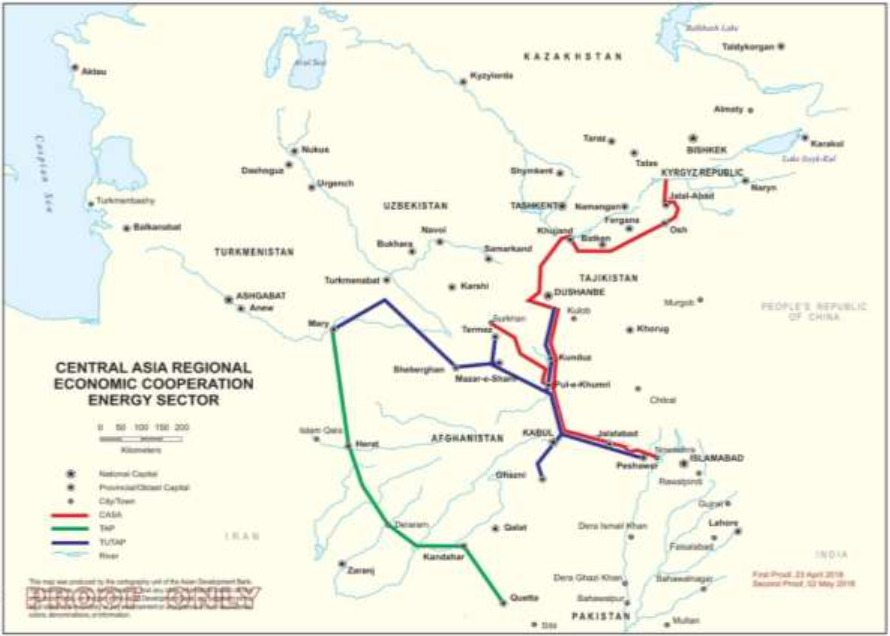

There is tremendous potential for regional cooperation among SAARC countries to promote the promote the process of decarbonization in the various countries. There is also an argument that India will not be able to achieve this target without energy trade with the surrounding countries. CPR argues “Beyond the well documented roadblocks to such a radical systemic change, a politically thorny aspect has been overlooked – one that could make or break India’s efforts towards a just energy transition. According to Aditya Valiathan-Pillai from the CPR: “People have long talked about expanded grids as a way of adding large amounts of renewable energy to your energy mix. And that’s simply because renewables are intermittent. The idea of having a pan-continental grid, or a multi-country grid at the very least, has existed for a very long time, and has only been amplified and gained traction with the rise of modern renewable technologies. It has a lot of political salience in the sense that it creates interdependencies between countries and is seen as a way of actually preventing conflict. The reason why this idea doesn’t always take the top spot in the debate is because of the huge political costs involved in creating something like this”. A long term net zero target for South Asia , will require installation of expensive balancing technologies [to solve the intermittency problem], such as large batteries, or pumped hydro storage. Those things are hard to build and are expensive. Through grid expansion further out to countries like Nepal and Bhutan, who naturally have a lot of hydropower, or say Bangladesh, which seems to be investing in natural gas, also a good balancing technology. But there are challenges that prevent this from becoming a reality – geopolitical dynamics between countries, their failure to find support in home constituencies, their inability to follow through their own commitment made at multilateral forums such as SAARC are to name a few. Even if these challenges are addressed, India is looking at a 2060 – 70 timeline, and that too if geopolitics aligns itself well.

References

- ADB, 2016. Assessing the Intended nationally Determined Contributions of Developing Members.

- WRI, 2019, What does net zero mean and 8 most common asked questions, answered

- The Wire, 2015, Why cant India meet its net zero targets alone?