The following blog aims to provide an overview of the historical background of regional Cooperation in South Asia’s electricity sector, the current status, including challenges and drivers, and the prospects of cross-border cooperation in the region, considering political, economic, and climate change-related aspects.

2. Background

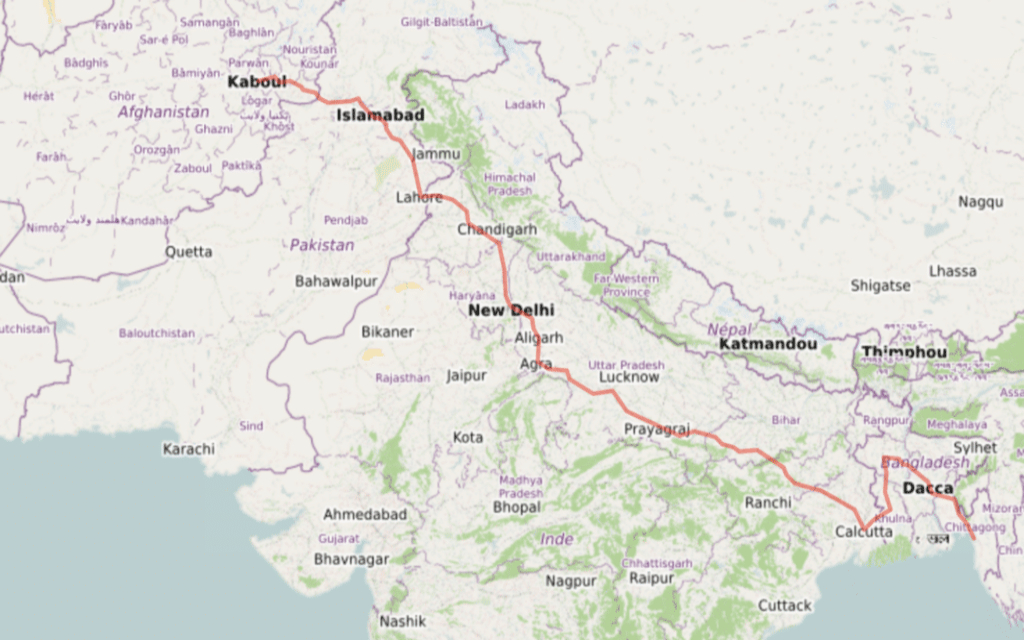

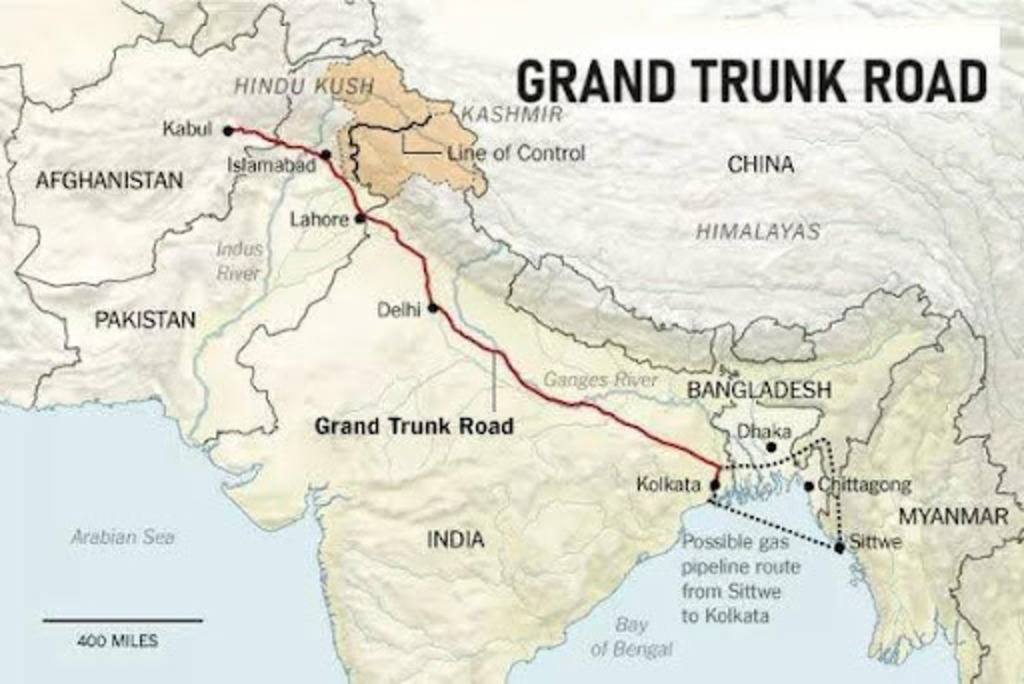

Looking at history, regional cooperation is not an unknown phenomenon. The ancient Silk Road connected East and West Asia, facilitated trade, and benefited the countries1. The “Sarak-e-Azam,” built during the 16th century by the Afghan Sultan Sher Shah Suri, is yet another example of connectivity in the region. It connected the cities of Agra and Sasaram in the first stage; later, the road was extended to Kabul. Today, the road is known as the “Grand Trunk Road,” connecting India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Unfortunately, colonialization and rivalries between superpowers in the last three centuries, security concerns, and post-colonial cross-border conflicts among the countries during the last decades have hampered connectivity in the region.

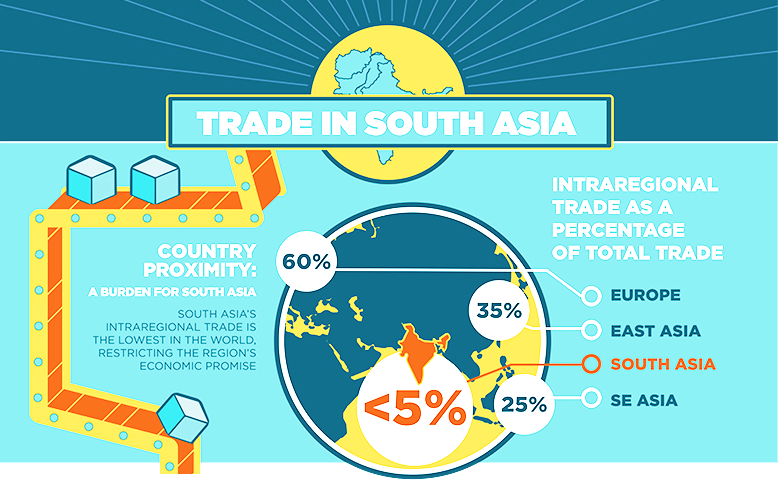

In the 20th century, the first institutionalized approach to facilitate regional Cooperation in South Asia started with the establishing the South Asian Cooperation for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1985 Dhaka, Bangladesh. Despite SAARC’s existence for decades, South Asia is still one of the least integrated regions in the world, where the share of intra-regional trade accounts for only five percent3 of the region’s total trade. Labeled as a study-driven regional institution, many scholars and policymakers question SAARC’s capacity to be an effective platform to foster regional cooperation.

Regional cooperation in the energy sector /cross-border electricity trade (CBET) in South Asia was, until recently, limited to bilateral cooperation between the countries, mainly India-Bhutan, India-Bangladesh, and India-Nepal. Thus, the cross-border trade is currently limited to the BBIN 4sub-region of South Asia.

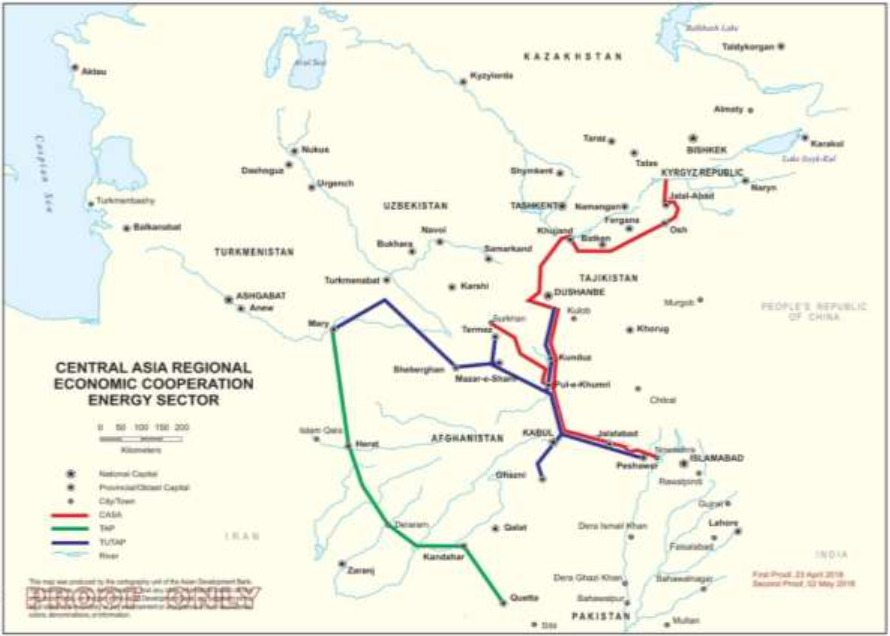

The CASA-1000 high-voltage transmission line from Central Asia is the first major interregional power project to facilitate electricity transmission between Afghanistan and Pakistan. For the time being, the extension of this line to other South Asian countries, such as India, is not contemplated.

The following will discuss the current status of CBET in South Asia, followed by an analysis of the main challenges and drivers and the prospects of CBET in the region.

3. Current Status of CBET in South Asia

As mentioned, CBET in South Asia is currently limited to bilateral trade between the BBIN countries and cannot be expanded beyond the sub-region. About 700 MW of electricity is traded between India and Nepal via different transmission routes. Bangladesh imports 1,160 MW from India, while Bhutan exports approximately 2,325 MW to India.5India and Sri Lanka lack a direct electricity connection, but there are plans for cross-border connectivity via undersea cables or overhead transmission lines.

In the financial year (FY) 2021-22, around 16,820 GWh of electricity was traded among BBIN countries. The electricity exchange within the BBIN nations has increased nearly 2.2 times since 2014, totaling 7,705 GWh. In FY 2021-22, India imported 7,597 GWh from Bhutan and exported 7,302 GWh to Bangladesh and 1,921 GWh to Nepal6. For the FY 2022-23, the net power transaction in the BBIN region was at 15,160 GWh7.

Table 1 below summarizes the CBET capacity and electricity trade volume within the BBIN sub-region.

| Particulars | Quantum (MW) | Electricity Transacted (GWh) in FY22 |

|---|---|---|

| India-Bangladesh | 1,160 | 7,302 (Export from India) |

| India-Nepal | ~ 700 | 1,921 (Bi-directional) |

| India-Bhutan | 2,325 | 7,597 (Bi-directional) |

Although current trade is limited to a bilateral level, several initiatives for trilateral trade in the BBIN subregion are also underway. One such initiative is the export of electricity from the 900 MW Upper Karnali hydropower plant (HPP) in Nepal to Bangladesh—a project developed by the Indian private developer GMR. Another project is the 1,125 MW Dorjiling HPP in Bhutan, aiming to deliver power to Bangladesh via India.

The first tangible initiative within the BBIN sub-region of South Asia to excel in the current bilateral-to-trilateral trade has been concluded recently with the signing of an MoU between Nepal, India, and Bangladesh. Nepal will export its surplus power from June to November via India to Bangladesh, whereas during the first phase, the trade is limited to 50 MW9.

Considering the political tensions between India and Pakistan, there will be no noticeable collaboration between the two countries in the near future. This situation is affecting not only the cooperation between the two countries but also disrupting connectivity on a regional level.

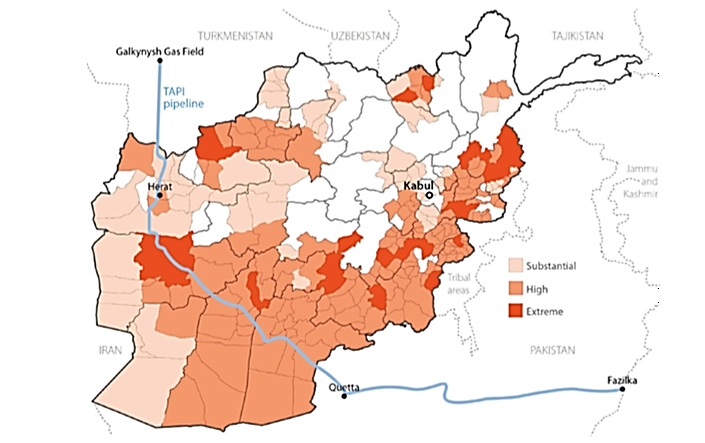

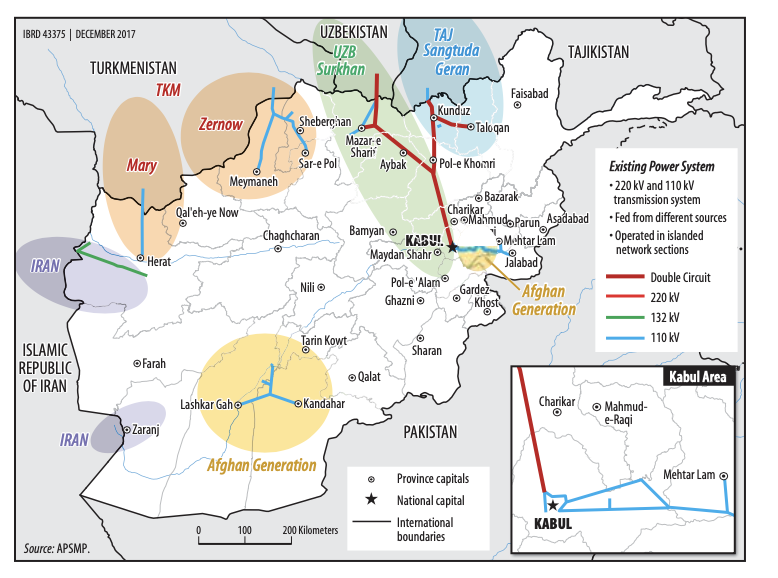

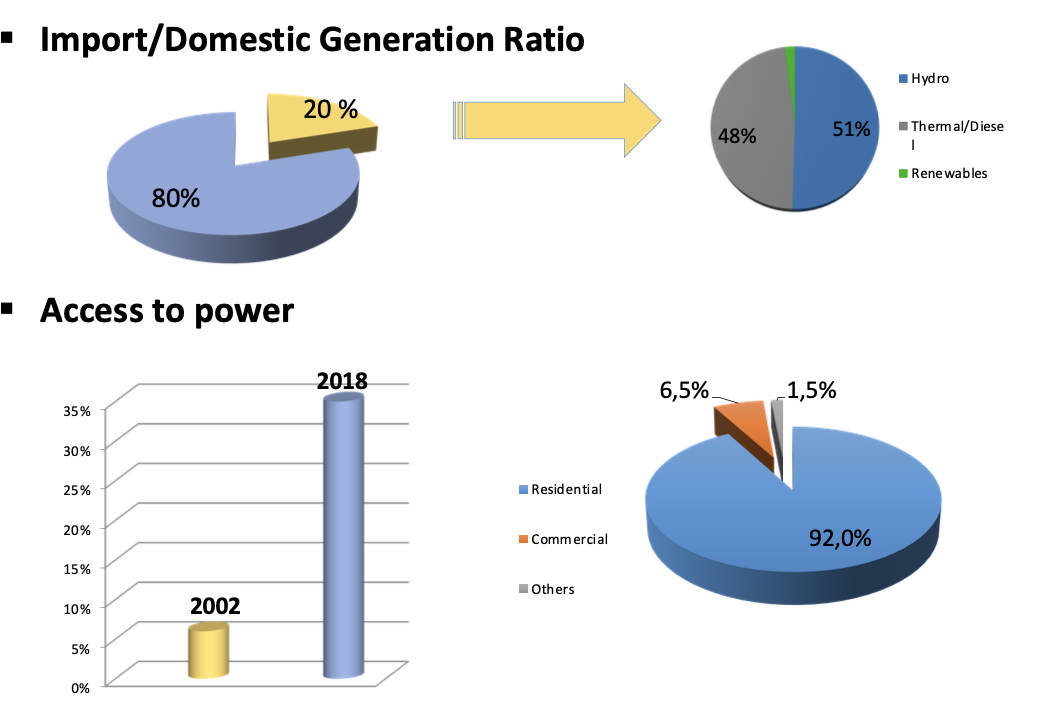

In addition, the political situation in Afghanistan since August 2021 is another serious obstacle to enhanced and seamless power trade in the region. Despite the country’s insecurity, Afghanistan was considered, during the last two decades, the key linkage between Central and South Asia, with major regional projects, such as the CASA-1000 transmission line, Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan Transmission Line (TAP), and TAPI.10 gas pipeline planned to be routed through Afghanistan. It was aimed that these regional energy projects would enhance energy trade and have a spill-over effect on other economic sectors in Central and South Asia. Although the World Bank announced in February 2024 the resumption of the CASA-100011 project The future of TAPI and TAP still needs to be clarified. Besides economic factors, geopolitical considerations will determine the future of these regional projects.

4. Drivers and challenges for CBET in South Asia

In addition to the aforementioned geopolitical rivalries in the region, various challenges and drivers (see Table 2 below) are decisive for Regional Cooperation in the power sector in South Asia.

The political, economic, and systemic asymmetry vis-a-vis India is a clear bottleneck. This multi-dimensional imbalance causes, particularly in the region’s smaller countries, hesitance to foster cooperation. The imbalance is also visible in the vast differences in quantity and quality of required electricity infrastructure, which not only makes an enhanced CBET difficult but also leads to serious challenges in attracting foreign investment in generation and transmission. Moreover, the need for more policy and regulatory frameworks in many countries on a national level is another challenge to seamless cooperation. For example, India is the only country in the region with dedicated CBET guidelines; no other country has yet developed a similar guideline that outlines the framework for regional electricity cooperation. Finally, the lack of a functioning regional institution that fosters collaboration, coordination, and trust and is positioned to draft an accepted and holistic decision-making process is another major obstacle for CBET in the region.

However, despite the existing challenges, many factors have been recognized by the countries as enablers/drivers to overcome the current impediment. This is particularly valid for the BBIN sub-region, considering the development since 2014, as indicated in the previous section.

The recent conflict in Ukraine has once again reminded the regional countries of their huge dependency on fossil fuel imports and its impact on the countries’ economies. Therefore, enhanced regional cooperation through electrification of the energy sector improves energy security and supports the countries in achieving the envisaged NDC targets. Regional cooperation is an important pillar, considering the complementarity potential in terms of resources and their demand in the region. Besides the required policy and regulatory framework, an essential pillar for seamless cooperation is upgrading and expanding the in-country transmission infrastructure, followed by expanding cross-border interconnection. A coordinated approach covering policy, regulatory, and infrastructure-related aspects would encourage international development partners and private investors to invest in the required infrastructure. The existing bilateral trade from the region and the experience from other regions can be utilized to improve current cooperation, even if only the BBIN countries are involved at this stage.

Considering India’s preference toward BIMSTEC, it would be realistic to commence the enhanced cooperation within this regional institution; however, it should also be noted that long-term isolation of Pakistan and Afghanistan would have not only political implications but would also limit the economic opportunities that regional Cooperation offer through connectivity to other regions, such as Central Asia. Therefore, it is essential to consider the most viable option for the time being without neglecting the implication of a possible isolation of Pakistan and Afghanistan. As BIMSTEC offers opportunities for Cooperation with Southeast Asian countries, the possible extension of Cooperation to Pakistan and Afghanistan will pave the way for collaboration with another important region- Central Asia.

| Enablers/ Drivers | Challenges |

|---|---|

| • Achieving energy security by reducing current dependency on fossil fuel imports and accelerating electrification of the remotest areas | • Pakistan-India political tensions are the central impediment towards seamless CBET in the region |

| • Meeting NDC targets by trading surplus clean energy and exploiting the untapped potential of renewable energy using domestic and cross-border transmission lines | • Political, economic, and systemic power asymmetry vis a vis India is perceived as a bottleneck for enhanced regional cooperation |

| • Increased number of cross-border transmission lines and established mechanisms | • Inadequate/ poor electricity infrastructure within each country and across borders for a seamless two-way flow of electricity and challenges in attracting foreign and private investments for building new hydropower/ RE projects and transmission lines |

| • Strong experience and ecosystem of bilateral trade and access to international best practices through the initiatives of development partners | • Inadequate policy and regulatory framework on a national level to facilitate enhanced CBET |

| • Regional institutions, serve as a possible option to anchor regional CBET initiatives | • Lack of dedicated engagement modality or institutional platform at the regional level to foster cooperation, coordination, trust, and a holistic decision-making process |

| • Electricity cooperation provides spill-over benefits and boosts cooperation in other sectors |

5. Prospects of enhanced CBET in South Asia and conclusion

As stated, the political tensions between Pakistan and India are considered the main impediment to enhanced regional electricity cooperation in South Asia. Therefore, cooperation between these two countries in a critical sector, such as the electricity sector, is not realistic for now. This situation hinders collaboration between these two countries and disconnects Afghanistan from regional Cooperation in South Asia. In addition, the existing disconnect between these countries impedes inter-regional Cooperation between South Asia and the energy-rich Central Asia, which would facilitate power trade and open up the path to collaboration in other key economic sectors.

Considering the current stagnation on a regional level, it can be concluded that the prospects of cross-border cooperation in the axis between Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India are not very promising until the leaderships of Pakistan and India resolve the existing political issues.

On the other side, the recent positive developments within the BBIN countries, focusing on an economic rather than political agenda, indicate that cross-border Cooperation in South Asia is not impossible. India, the key regional player in the sub-region, is pursuing the enhancement of cooperation and has shown a willingness to facilitate trilateral power trade between the regional countries. The MoU between Nepal, India, and Bangladesh on the transmission of power from Nepal to Bangladesh via India can serve as the basis for future multilateral electricity cooperation in the sub-region. Moreover, the countries view CBET as an opportunity to enhance energy security and expedite the process of clean energy transition in their countries.

The establishment of the BIMSTEC12 Energy Centre in Banglore, India, indicates India’s commitment to enhancing regional power cooperation. India favors BIMSTEC due to its geoeconomics focus and alignment with the country’s Act East policy.

India’s active engagement in the BIMSTEC regional platform, which also includes the Southeast Asian countries of Myanmar and Thailand, further reduces the chances of SAARC playing a pivotal role in enhancing regional electricity cooperation in South Asia. This, in turn, confirms the statement above that in the near future, regional cooperation will be limited to the BBIN sub-region and will not expand to Pakistan and Afghanistan- a situation which could be considered as an opportunity by other players, such as China, to achieve its geo-economic objectives in the broader region. The ongoing discussion13 the expansion of the China-Pakistan-Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a clear sign of China’s willingness to expand its influence in this belt, which might further reduce the prospects of an interconnected South Asia.

Therefore, it is of utmost importance to pursue enhancing cooperation in the BBIN sub-region without neglecting the importance of including Pakistan and Afghanistan in the regional framework in the long-term. This is a challenging task, but the only option is to facilitate long-term peace, prosperity, economic development, and a just green transition in the region through the creation of interdependency, where each country views regional cooperation as an opportunity rather than a burden.

1The Silk Road: Bridging Middle East and Asia

2 https://aisrs.org/31/the-grand-trunk-road-gt-road-a-historical-highway-of-harmony-and-heritage

3 https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/south-asia-regional integration/trade#:~:text=Intraregional%20trade%20accounts%20for%20barely,of%20at%20least%20%2467%20billion.

4 Bangladesh-Bhutan-India-Nepal

5 USAID-SARI/EI, Role of Cross Border Electricity Trade in Enabling the Renewable Energy Deployment & Integration in India/ South Asia Region, July 2022.

6 POSOCO Monthly Reports of March 2021 and March 2022, https://posoco.in/reports/monthly-reports/

7 POSOCO Monthly Report of March 2023, https://posoco.in/reports/monthly-reports/monthly-reports-2022-23/

8 POSOCO Monthly Reports of March 2021 and March 2022, https://posoco.in/reports/monthly-reports/; USAID-SARI/EI, Role of Cross Border Electricity Trade in Enabling the Renewable Energy Deployment & Integration in India/ South Asia Region, July 2022

9 https://indianexpress.com/article/news-today/nepal-india-bangladesh-agreement-cross-border-electricity-trade-9602203/

10 Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India

11 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2024/02/15/world-bank-group-announces-next-phase-of-support-for-people-of-afghanistan

12 Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation

13 https://www.voanews.com/a/extension-of-china-pakistan-corridor-to-afghanistan-presents-challenges-/7178387.html