Taxonomies have become one of the latest policy measures that are being onboarded on the bandwagon of accelerating energy transitions across the world. Essentially, these are policy documents in the form of a framework that lay out a defining criterion for an economic activity or investment to be labelled as ‘sustainable’ or ‘green’.

The landmark taxonomy document which acted as a benchmark for various other countries and regions was the European Union’s Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities which was released in 2021. Lately, in 2023, the European Commission passed a legislation to implement the taxonomy report. Since the EU Taxonomy came out in the public domain, various other nations have followed suit including Indonesia, China, Singapore, Malaysia, amongst a few others. A similar taxonomy is in consultation stage in Australia and a common framework for Sustainable Finance Taxonomy was also drafted for the region of Latin America and Caribbean countries by the financial support of the European Union.

The Government of India has also taken initial steps in this regard. As per the Economic Survey of India of the year 2021-22, a Task Force on Sustainable Finance was created by the Department of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Government of India which was mandated to suggest a draft taxonomy for India, amongst other sustainability-related mandates. However, the draft taxonomy is yet to see the light of the day.

As India maneuvers to put in place a Sustainable Finance Taxonomy of its own, it is highly pertinent to analyse some of the existing taxonomies and put forth a vision that should guide a fair, effective and just taxonomy for India. This blog attempts to provide a very broad framework for doing so.

Relevance of a Taxonomy

The rationale for institutionalizing such a framework in the form of a taxonomy is multifold.

First, it places a system of safeguards, indicators and other relevant screening criteria that can be used to differentiate between a ‘green’ activity and other economic activities. While some activities like coal-based power generation are outrightly non-green, such a system also acts as a check on certain types of activities being passed on as ‘green’ which might still have a substantial carbon-footprint. Commonly known as ‘green-washing’ in the circle of climate enthusiasts, it is widely believed to be a phenomenon which hurts a country’s efforts on sustainability.

Second, this provides a platform for harmonizing the various ways in which different countries define sustainability and preparing a ‘common but context-conscious’ framework through which can be used as a lens to monitor green economic activities and green investments.

Third, a taxonomy can be used as a market-based tool to provide a positive market signal to domestic as well as global investors that seek to expand their green portfolio, by providing a clear framework of defining a sustainable economic activity.

How will a taxonomy work?

A taxonomy is essentially a policy tool which enables investors, governments and other players to assess whether an investment into any type of an economic activity is sustainable or not. For this, a taxonomy has to define what it means by sustainability. This would include a clear set of objectives that an economic activity must accomplish, in order to be labelled as taxonomy-aligned activity, and in turn, the investment can be labelled as a green investment.

The existing taxonomies usually cover environmental objectives of climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation for defining sustainability. However, in a significant development, European Union also released a draft social taxonomy separately, which talked about social objectives as well. It might be worth to embrace a more open and holistic definition of sustainability, one that takes into account social, cultural, environmental, ecological and other relevant aspects of sustainability. Therefore, a taxonomy should clearly lay out the objectives which any economic activity aspires to accomplish.

The next element which is crucial in a taxonomy is providing the knowhow of indicators or parameters that can be used to assess any economic activity. For climate change mitigation, lifecycle emissions of any activity can be directly used as a parameter to adjudge whether an activity is sustainable or not. For example, in the EU taxonomy, any clean power generation technology including solar, or wind power, is only labelled as ‘sustainable’ as per its Taxonomy if the projected lifecycle emissions of that power generation facility are less than 100gCO2e/kWh. This technical minimum of emissions per unit of electricity generated were scientifically computed by experts in the EU.

Similarly, in Indian context, for various economic activities across a range of sectors including agriculture, manufacturing, power generation, transport, services, amongst others, a technical minimum of lifecycle emissions can be computed, in order to place a defining framework of sustainability for that economic activity. Vasudha Foundation is actively working with NITI Aayog to come out with updated lifecycle emissions from the power generation sector, across multiple technologies.

While laying out parameters and quantitative technical indicators for emissions could be relatively straightforward, it will be a highly complex task to determine the indicators and parameters for social, cultural, ecological and other such aspects which would require a blend of quantitative and qualitative indicators. For instance, if an economic activity of electric vehicle manufacturing facility claims that it aims to meet social objectives of providing employment opportunities, in addition to the obvious objective of reducing transport sector emissions, the technical indicators for measuring whether the social objectives are effectively met will have to take into account not just the number of jobs, but also quality of jobs, levels of occupational hazard, opportunities for skill development, collective bargaining power of workers, and other such metrics.

Another critical element of the way in which a taxonomy works, is that the economic activity under assessment must clearly indicate which one of the objectives of sustainability does it primarily aims at achieving. When it does it, the taxonomy also assesses the activity on the ground that it must not be doing harm in case of other objectives. For instance, while a polluting industry may be adhering to social objectives of providing local employment opportunities, it cannot be labelled as ‘sustainable’ because it will be causing significant harm to the environmental objectives.

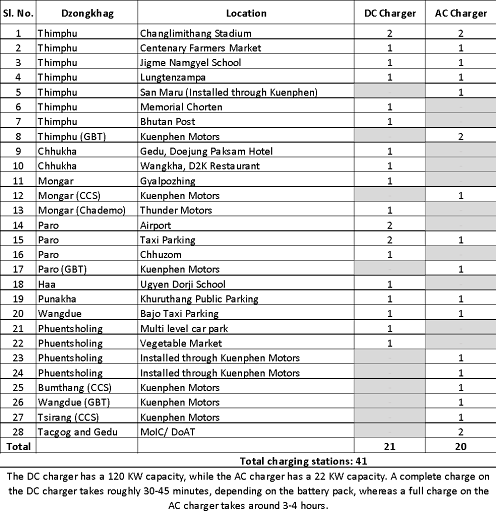

The following table provides a quick glance at some of the existing taxonomies that have been released:

| Name | Objectives | Economic Activities Covered | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy | Environmental objectives -sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources, the transition to a circular economy, pollution prevention and control, and the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems, | Energy, Manufacturing, Buildings, Disaster Risk Management, Water Supply and Sewarage, Transport, Services, Forestry, ICT & Professional Activities | Click |

| SDG Finance Taxonomy China | All the SDGs | Manufacture of energy efficient equipment; Clean production industry; Clean energy industry; Industry of ecology and environment; Green upgrade of infrastructure; Green services | Click |

| Principles-based Sustainable and Responsible Investment Taxonomy – Malaysia | Environmental Objectives – Climate change mitigation, Climate Change Adaptation, Protection of Healthy Ecosystems and Biodiversity, Promotion of Resource Resilience and Transition to Circular Economy; Social Objectives – Enhanced Conduct towards Workers, Enhanced Conduct towards Consumers and End-users, Enhanced Conduct towards Affected Community and Wider Society | Non-exhaustive List – Consumer Goods and Manufacturing, Construction and Real Estate, Utilities and Infrastructure, Financial Services, Technology and Telecommunications, Education, Healthcare, Plantations and Agriculture | Click |

| Singapore-Asia Taxonomy | Climate change mitigation; Climate change adaptation; Protect healthy ecosystems and biodiversity; Promote resource resilience and circular economy; Pollution prevention and control | Energy, Transport, Real estate and Construction, Industry, Forestry, Carbon capture and Storage, ICT, Waste, Water, Agriculture | Click |

Finally, a taxonomy must be used as a market-based tool only, and should not be imposed legally because such an imposition will be counter-productive, i.e. instead of attracting green investment, it might be scaring investors away. A safety clause may be inserted in the taxonomy that all economic activities that claim to be taxonomy-aligned, and hence ‘sustainable’ should follow all the prevailing regulations and laws of the land, including laws for environmental protection, social protection, labour rights, ecological regulations, amongst others. Furthermore, a taxonomy should not be seen as a replacement to domestic ESG regulations, but merely as a tool that further strengthens it and seeks to expedite inflow of climate finance in the country.

Way forward

India must endeavor to create a taxonomy which derives itself from the indigenous principles of justice, equality and prosperity. ‘Vasudeva Kutumbakam’ – the tagline for the recently concluded G-20 meet in New Delhi can also act as a source of deriving the principles of a taxonomy, especially in defining what ‘sustainability’ would mean.

Safeguarding national interests, promoting ecological and environmental justice, not accepting a western cannotation of sustainability and charting out an indigenous taxonomy of India, which represents the voices from the ground, and not from the Global North, is a good way to go about it. This implies that a highly deliberative process that takes opinions from a large section of population, especially the marginal and vulnerable groups, will go a far way in defining ‘sustainability’, and how can a sustainable economic activity be identified.

In doing so, India’s taxonomy could be a path-breaking development and another accord for the nation’s efforts on sustainability – a fair and ‘just taxonomy’, instead of just another taxonomy.

A truly Indian taxonomy will include best practices from existing taxonomies but should derive itself on Indian ideas of sustainability. This resonates well with the Indian philosophical idea of ‘Vasudeva Kutumbakam’ which goes like this:

अयं बन्धुरयं नेति गणना लघुचेतसाम् ।

उदारचरितानां तु वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम् ॥

English Translation

This one is a relative, friend and brother;

this other one is a outlander” is for the mean-minded.

For those who’re known as magnanimous,

the entire world constitutes but a family.