Energy sources like electricity and LPG along with other renewables are recognized as modern forms of energy which unfortunately is used sparsely in developing countries (ESMAP, 2003, p.7; Day et al., 2016, p.257). Improving the availability of reliable and affordable energy carriers for the realization of modern energy services has been the essence of achieving global energy access. Access to energy supply in accordance with Bhatia & Angelou (2015), is “ability of end user to utilize energy supply that can be used for desired energy service” (p.viii). Access to modern energy sources possess undeniable nexus with socio-economic development of developing nation. Since, access to modern forms of energy is closely associated with overall development of nations, there needs to be a clear understanding of existing energy access situation, level of energy access and energy services. Baseline data with reflection of the modern energy access situation can therefore be helpful in strengthening the nexus between energy and socio-economic development. Regardless of electricity supplying technology, in the past electricity access has been measured through binary variables “Yes” or “No” or “have access” or “don’t have access” (Jain et al., 2015). Binary approach is ineffective in capturing true scale of electricity deprivation at certain village or household level due to its inability to address multi-dimensional aspect of electricity access. The binary definition of measuring electricity access is not able to capture difference in quality and quantity of electricity supplying technologies (Practical Action, 2013, p.28). With a binary approach of measuring electricity access, a household with electricity supply from 20 Wp SHS or solar lantern and another household with electricity supply from national grid, both will be viewed as households having similar type and level of electricity access which is not true. There exists a big difference in terms of electricity services that a household can derive from electricity produced by SHS and national grid. The binary approach fails to capture other dimensions of electricity supply which includes ability of supply system to support all kinds of electrical appliances (low power to very high power), erratic nature of supply system and duration of supply. Nepal as of now is following binary approach to measure electricity access. Household are categorized as having access to electricity if there is presence of electricity either from national grid or off-grid electricity supply system. But in recent time, Government of Nepal has adopted MTF to measure the electricity access to keep track of universal target set by SE4ALL and SDG (Goal: 7) (NPC, 2018, p.2). The stark disparity between rural and urban areas can be better scrutinized following a multi-dimensional approach to measure electricity rather than binary approach. The electricity access disparity share between rural and urban areas might be different to that of disparity figure given by binary approach (World Bank, 2017, p.24). A village in India was said to be electrified if 10 percent households had access to electricity. As a result, 96.7 percent of Indian villages were found to be electrified which was not the real case (Jain et al., 2015, p.31). Such binary approach yields spurious statistics regarding share of households having electricity services. Due to presence of anomalies in binary approaches, multi-dimensional access measuring metric; Multi-Tier Framework (MTF) is gaining popularity in measuring electricity access.

Multi-Tier Framework (MTF): Planning for Electricity Access

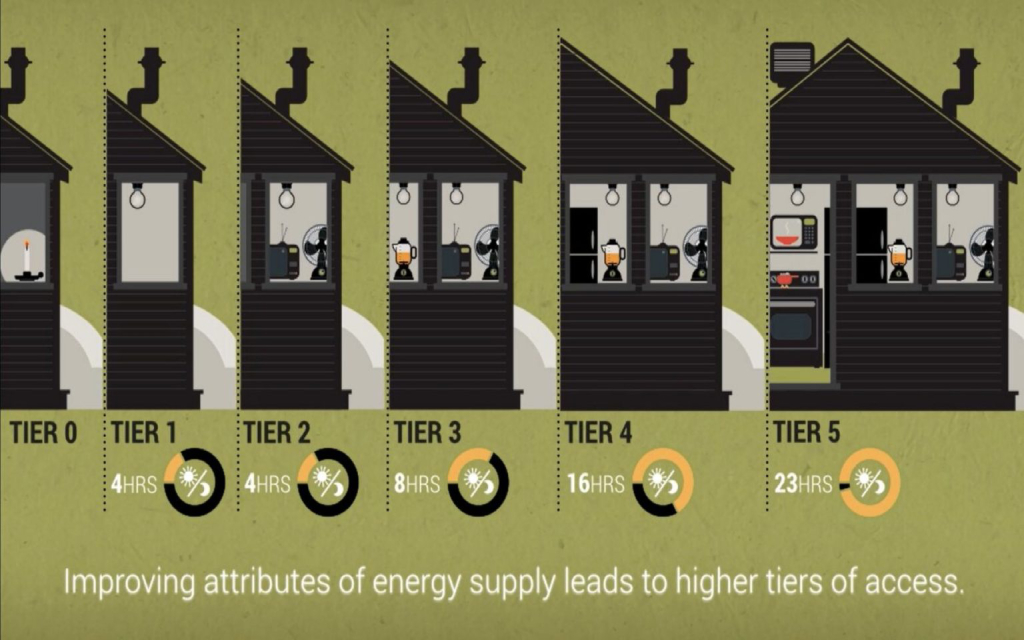

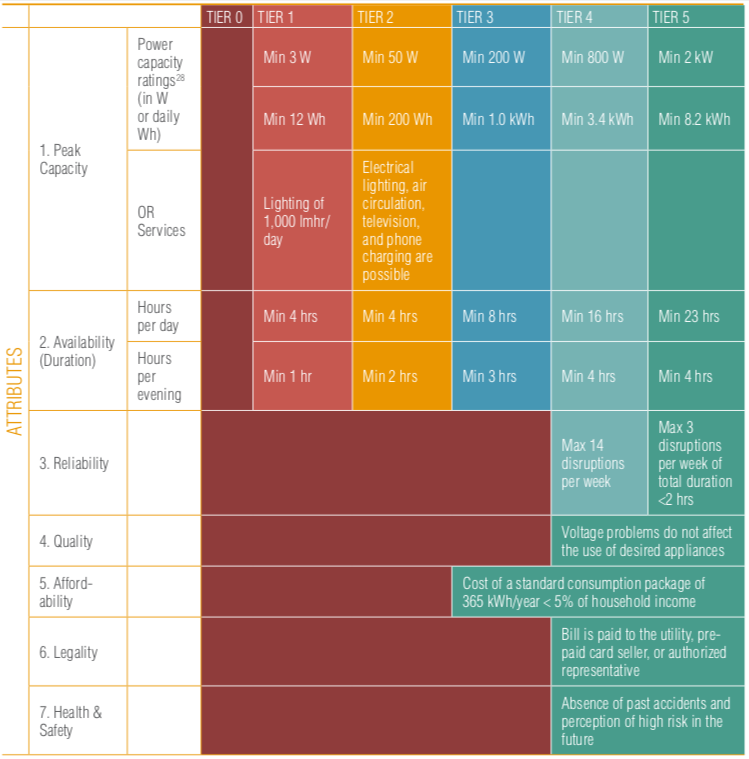

Under SE4ALL, the Global Tracking Framework (GTF) 2013 introduced Multi-Tier Framework (MTF) to measure energy access (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015, p.1). The MTF has provided number of attributes and dimensions, based on which electricity access is measured. There are seven attributes; capacity, duration, reliability, quality, affordability, legality, and health & safety; each of which defines various dimension of electricity supply system. Electricity access is measured with respect to seven different attributes across which electricity supply situation for a household is analyzed. Each attribute is analyzed, and results are expressed in terms of tier; Tier 0 being the worst level of access while Tier 5 is best access level at household level. According to the decision rule of MTF, final tier of electricity supply is determined by the lowest tier obtained across all seven attributes of electricity supply (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015, p.5). The MTF attributes for electricity access measurement are shown in Figure 2-1. Figure 2-1: MTF Matrix for Measuring Electricity Access for Households Source: (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015, p.6).

MTF approach to measure electricity access enables energy planners and policy/decision makers to identify appropriate level of electricity in the form of tier and amount of investment required to reach the target tier (World Bank, 2017, p.xv). Defining energy access with respect to attributes will be helpful in identifying interventions such as technology implementation, policy development or capacity building endeavor required to improve electricity access level. Scrutinizing every electricity access attribute is useful in identifying major challenges that is impeding improvement in energy access. For a country or region, MTF can elucidate the reason for them being unable to upgrade electricity access tier (World Bank, 2017, p.24). According to Bhatia & Angelou (2014), “multi-tier measurement of energy access allows government to set their own target by choosing any tier above tier 0” (p.7). Based on available resources, timeframe and geographical challenges, local government may decide which tier they would like to aim for based on baseline information of household tier.

Source: (Bhatia & Angelou, 2015)

The MTF has already been experimented as tool to devise energy access plan in Bangladesh, Kenya, and Togo (Practical Action, 2014, p.2). Classification of households into tiers gives wider perspective of type of energy access prevalent in certain area/village/location of interest. This helps to visualize challenges and factors that are impeding to improve the energy access situation of households in areas affected by poor supply of energy. As emphasized by Jain et al., (2015), the advantage of using MTF is the identification of variation involved in energy supply and access situation in certain region. Moreover, MTF has been used to enunciate country action agenda to meet SE4ALL objectives (Pelz et al., 2018a).

On a global scale, the level of electricity access is desired at Tier 3, but MTF provides flexibility to member states to set up plans to reach the global target as much as possible (NPC, 2018, p.3). Kenya in its SE4ALL action agenda has planned to improve its energy access situation according to the MTF-tier concept. By 2030, Kenya plans to secure 35 percent household to be at tier 3, 15 % at tier 4 and 10 percent at tier 5 while 40 percent below tier 3 (Practical Action, 2014, p.64). For the member states of United Nation agreeing to comply SE4ALL and SDG (Goal: 7) initiatives, tools such as MTF should not only be able to measure the progress but also assist member state governments and concerned organization to devise concrete plan and policies by providing noticeable evidence (Pelz et al., 2018b).

Multi-Tier Framework Critique

The MTF provides a tool that can be used to measure energy access across the globe. Although MTF can address shortcomings of binary metrics to measure energy access, there exists argument regarding generalization of MTF approach to measure energy access (Pelz et al., 2018; Tait, 2017; Groh et al., 2016). Generalization of MTF to measure energy access in different countries across the world reduces its usefulness as a tool for national energy planning. MTF requires certain level of national adaptation to obtain tangible results regarding energy access situation with respect to diversity existing between different regions and countries (Groh et.al., 2016; Tait, 2017). Nevertheless, the classification of tiers to evaluate access to energy services is necessary and valuable to understand the baseline status of energy access for a particular region and develop plan for improvement in future. Generalization of the global energy access measuring metrics falls short in addressing gaps existing between the developed, developing and least developed country. There exist country specific factors such as geography, culture and socio-economic status of the nation and its citizen which may not be addressed by generic tools such as MTF (Tait, 2017). Furthermore, the energy service need may vary from one household to another due to their preference of appliances or culture (Pelz et. al., 2018, p.3). The way of living, cultural behavior, the quality of energy services that the end user is receiving, desire to climb up the energy ladder and use of modern appliances also impacts the result of electricity access measurement. The measurement of energy access based on MTF attributes might need adjustment as per country specific context due to existence of diverse energy needs and factor affecting those needs. The MTF approach has been adapted in the past to measure electricity access level. Tait (2017) analyzed energy access status in South Africa using just four attributes: fuel consumption, affordability, safety, and reliability without categorizing household into MTF tiers. According to the assessment made by Tait (2017), the indicators used for the measurement of electricity access were analyzed based on the score such that 1 being better access and 0 being the worst. Jain et al., (2015) made use of MTF and adapted it to Indian context by using four tiers instead of six tiers to visualize level of energy access. Furthermore, the availability attribute has also been analyzed over a period of a day which is slightly different from availability attribute mentioned in MTF that considers electricity supply in evening hours. There exists argument over maintaining simplicity and uniformity in use of availability attribute across the world (Jain et al., 2015; Pelz et al., 2018). The development status gap between global north (developing and least develop country) and global south (developed country) and global south represented by developing and least develop country pose challenges in generalizing MTF around the world. Global south is more inclined towards commissioning modern energy infrastructure to fulfil energy needs of their population with priority on energy efficiency while global north is more focused on improving energy efficiency and thereby reducing their share of carbon footprints (Day et al., 2016). The challenge of generalizing further exacerbates as the MTF in its current state is not able to address impact of energy efficiency endeavors on requirement of capacity of energy supply system (Pelz et al., 2018). Establishing a common threshold value for energy access measuring attributes has been subject of argument. There have been several examples where the threshold value to determine level of electricity access has been altered by researchers. In Indian context, the legality attribute has been emphasized while in South African context legality attribute has not been considered with an argument of illegal connection for electricity being better source for lighting compared to primitive alternative like candle. Similarly, health and safety attribute were not captured citing in Indian context in absence of comprehensive data that could address health and safety attribute (Jain et al., 2015; Tait, 2017). Depending upon the context and situation one may decide what kind of information is required to compute MTF attributes with less complexity.

The MTF tier approach to measure electricity access clearly defines the kind of electricity service that can be derived from different tier of electricity access. The electricity access tier in these households needs gradation. But from planning perspective knowing a target tier for rural households is inevitable. Understanding appropriate target tier for electricity access is essential as it provides strong basis to develop electricity access vision and subsequently vision driven interventions in the form of plan and policies.

References:

- Bhatia, M., & Angelou, N. (2014). Capturing the Multi-Dimensionality of Energy Access. Livewire, 1–8.

- Bhatia, M., & Angelou, N. (2015). BEYOND CONNECTIONS Energy Access Redefined

- Day, R., Walker, G., & Simcock, N. (2016). Conceptualizing energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework. Energy Policy, 93, 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.019

- ESMAP. (2003). Household Energy Use in Developing Countries – A Multicounty Study, (October)

- Groh, S., Pachauri, S., & Narasimha, R. (2016). What are we measuring? An empirical analysis of household electricity access metrics in rural Bangladesh. Energy for Sustainable Development, 30, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2015.10.007

- Jain, A., Ray, S., Ganesan, K., Aklin, M., Cheng, C., & Urpelainen, J. (2015). Access to Clean Cooking Energy and Electricity. ACEESS – Survey of States, 1–98. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0NV9LF 93 Javadi, F. S., Rismanchi, B., Sarraf, M., Afshar, O., Saidur, R., Ping, H. W., & Rahim, N. A. (2013). Global policy of rural electrification. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 19, 402–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.11.053

- National Planning Commission. (NPC). (2018). Universalizing Clean Energy in Nepal. Retrieved from https://www.npc.gov.np/images/category/SUDIGGAA_final_version.pdf

- Pelz, S. (2018). Inclusive Energy Access Planning. Retrieved from https://reiner-lemoineinstitut.de/en/inclusive-energy-access-planning/

- Practical Action. (2013). Poor People’s Energy Outlook 2013. Retrieved from http://cdn1.practicalaction.org/5/1/5130c9c5-7a0c-44c9-877f-21b41661b3dc.pdf

- Practical Action. (2014). Poor people’ s energy outlook 2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Tait, L. (2017). Towards a multidimensional framework for measuring household energy access: Application to South Africa. Energy for Sustainable Development, 38, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2017.01.007

- The World Bank. (2017). State of Electricity Access Report 2017. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/26646/114841-WP-v2- FINALSEARwebopt.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y